The Sound of Us —by Kevin James Thornton

My first memories of music are from a Southern Baptist church in Evansville, a small town on the Kentucky/Indiana Border, right where the Ohio River makes a curly bend. The carpet in that church was bright red and the stained glass understated and unremarkable. Instrumentation was just a piano and an organ and the melodies were in unison. Every service ended with “Just As I Am,” and to this day the tune of it both haunts me with irony and strikes a nostalgic chord.

Although secular music was frowned upon, at home there was a stash of records. I learned to sing harmonies with Crosby, Stills and Nash and would practice chords on my grandpa’s Gibson. To this day the wood of that guitar has a musty nicotine smell.

By the time I was in high school in the late 1980s, we had left the strictness of the trapped-in-time Southern Baptists for a slightly more modern nondenominational church. They had a youth group. Most of my Friday nights were spent with them around a campfire with acoustic guitars singing more simple and repetitive “praise and worship” songs.

I was drawn to roots music. Music that was born out of wood, strings and a campfire… with just a touch of the Holy Ghost.

I wore out the cassette tape of the Indigo Girls 1989 self titled album. I wasn’t aware that they were lesbians. That was a different time. There wasn’t really any sort of overt queer representation in late 80s small town Indiana. As my sexual self awakened the deep conflict began, and over time I associated roots music as the sound of my oppressor. Country music identified those who would never accept me.

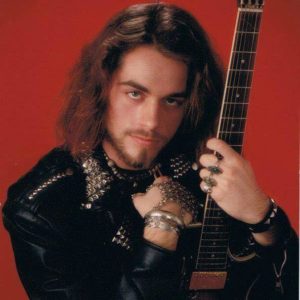

I began to explore more ambiguous artists like The Smiths and The Cure, and after high school, like many other small town gays of that era, made my way to New York City. My hair was long. I wore a biker jacket and combat boots. My tough exterior would often confuse the drag queen gate keeper at the Limelite, but she usually let me in.

The sound of being a white gay cis man was a techno beat. Looking back, I see why that simplistic pulse drew us to it. It was an identity war cry, calling us from oppressive communities to a place of acceptance. In dark clubs across America through the Clinton era, the four-on-the floor dance beat was the sound of who we were.

Today, it still is I suppose. Pride festivals are commonplace, even in small southern towns. They are colorful spectacles with barely dressed muscle men gyrating on floats– in the middle of the day! In front of families! A far cry from where I came from. All of this set to an electronic dance beat.

I never quite identified with all that. It never felt like me. When I started making my own albums, reclaiming roots music felt powerful. On my 2004 album “Had A Sword” the Nashville Scene wrote “His songs allude to dependent love, homosexuality, masochism and God- echoing with melodies from the Southern Baptist Hymnal.” and a decade later took the folk country vibe a big step further with my current project Indiana Queen.

It’s then when I began to see the phrase “queer country” emerge on the internet. Sure there were celebrities slowly crawling out of the closet along with country music divas giving their approval. But this was different. There was an actual sound to a lot of it. There’s the guitars, banjos and fiddles but things are often turned on their head a bit— queer as in quirky as much as queer as in sexuality and gender. Voices often warble in a way they might on an old Appalachian recording rather than on a slick Nashville record. Perhaps it’s lo-fi out of necessity, but it’s part of the vibe.

Not to say polished production or a more mainstream sound would disqualify it. A more important aspect of the newly forming genre is inclusion. Everyone is welcome here. Tell us a story about where you came from and we will listen and accept you. It’s in that storytelling itself that queer country finds its power.

And not surprisingly, it seems to draw all of the “others” from the LGBTQ+ community. If you don’t find yourself in club music, maybe you will in the sound of wood, strings and fire– reclaiming the sound of your roots. For many, queer country is the sound of us.

-Kevin James Thornton