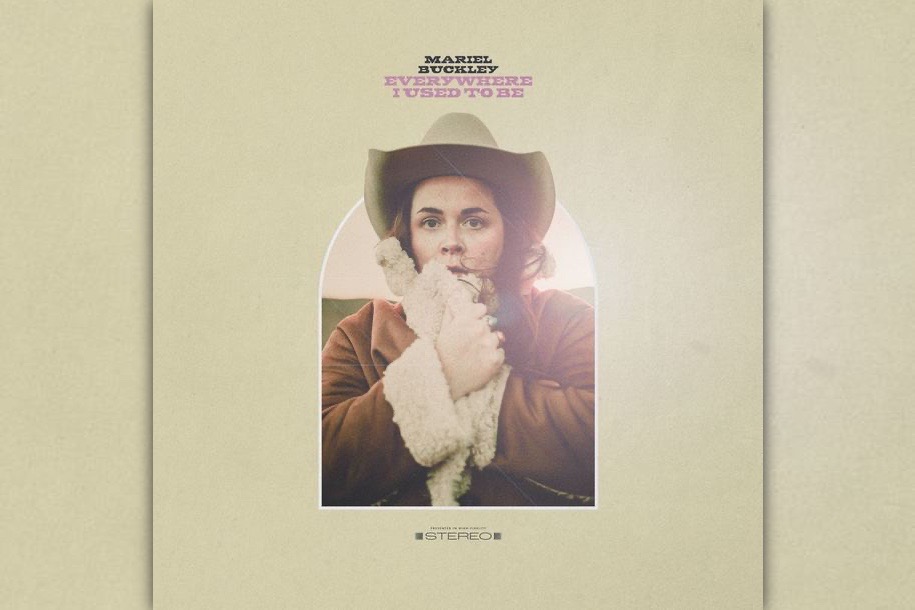

Album Review: Mariel Buckley Embraces Ambiguity on ‘Everywhere I Used to Be’

By Tyler Morgenstern

Seen from the outside, the city of Calgary, Alberta is the stuff of country music myth.

Look east and you’ll find an endless expanse of open prairie—a patchwork of golden canola and tawny grasses punctuated by worn-out, barbed wire fences and grain elevators long since decommissioned. Look west to see the Rockies rise not at all and then emerge, all at once, out of rolling green foothills. Look up: skies so wide, so wild, that they seem to have been invented in a Nashville writer’s room. Small wonder that these vistas have reared such legendary talents as Ian Tyson, k.d. lang, and Paul Brandt, to name just a few.

Seen from the ground, however, things are rather more conventional and ambivalent than this star-studded pedigree would suggest. Growing up Calgarian means, among other things: smoking bad weed in the sprawling parking lagoon that surrounds your local shopping plaza while the tinny sounds of Top 40 country radio stream in through trashed speakers. It means, once a year, donning your dad’s old Stetson and attending the Calgary Stampede, the world-famous rodeo and exposition that mostly consists of finance guys and real estate brokers playing cowboy to the sounds of Florida Georgia Line in parking lot beer gardens.

It also, maddeningly, tends to involve realizing, once you’ve been too long gone, that some part of you quietly cherishes it all. Or, at least, the image of it that hangs in the rear view.

On her new album, Everywhere I Used to Be, Calgary-based songwriter Mariel Buckley plumbs this queasily nostalgic terrain for all it’s worth. Due out August 12, Buckely’s first new music in four years hones in with unsparing focus on the charged minutiae of a life lived between worlds, spinning memories of skate parks, strip malls, and honky tonks into hard-edged reflections on surviving your own “Prairie Town Dreams.”

Produced by Marcus Paquin, Everywhere I Used to Be tugs at the edges of country-western sensibility, grabbing hold of the places where the whine of a pedal steel unexpectedly shades over into the thrum of a programmed synth. The result is an album that lives somewhere between the “motel bars” and “dingy lounges with dirty floors” of which Buckley sings on the anthemic single “Shooting at the Moon,” and those more homely, angst-ridden spaces—the suburban garage, the backseat of your first car, the Circle K where you buy your cocaine—where shoe-gazier tendencies often take root.

It’s not an effort to modernize country, exactly. It is even less an attempt to tack on some awkward prefix: alt-, post-, neo-, etc. Instead, Everywhere I Used to Be derives its aesthetic texture from the troublesome in-betweens that Buckley so bracingly interrogates on tracks like “Hate This Town.” Forceful title notwithstanding, here Buckley dwells in a riven ambiguity, unable to discern where her internal world ends and her surroundings begin. This makes the task of locating an object of hate a rather slippery one. What is despised on the exterior threatens—just a moment later—to fold back on itself, turning up much closer to home. “I don’t wanna hate this town,” she sings in coppery hues, “I’m just trying to keep my head down. But what’s the point when everybody knows your business?” And then the fold: “Goddammit I hate myself, goddammit I hate this town.”

At the edge of things, anonymous but somehow all-too-visible in her queerness, Buckley finds her hate suddenly toothless, or at least unreliable. What should be a tool for cleaving oneself off from the strip malls and streets, “lined up with neon crosses,” instead just ends up tightening the screws. Such stories of ambivalence—of aborted attempts at leaving, of fleeing only to find yourself back at square one, of chasing something new and discovering its sameness—carry the day on Everywhere I Used to Be.

Consider the title track. On the one hand, it is a familiar tale of an artist striking out on her own and paying her dues with countless gigs in one-stoplight western towns. On the other, it indulges the same bracing, aromantic equivocation at the heart of “Hate This Town.” As Buckley barrels from show to show across the prairie, everything begins to circle back on itself: “There’s a church, Chinese food and liquor, all pressed up to the same strip. Like every western town, I guess. Why change it if it still seems to fit?”

This is no ‘Nashville-or-bust’ narrative. On the contrary: everywhere Buckley might go turns out to be everywhere she’s already been. There is no clear sense of direction, no name-in-lights resolution to the plodding task of simply doing the work. The effect is compounded on “Going Nowhere,” where a circular lyric about the pointlessness of so many late-stage relationship arguments (“I’m so sick of talking, it’s all we ever seem to do. I don’t know. What about you?”) doubles back on itself in its closing moments, dead-ending all at once like a suburban cul-de-sac.

In less capable hands, this all might read as simple cynicism. But filtered through Buckley’s stirring vocals and Paquin’s elegant, surprising production, these stories feel less somber than simply true; so disarmingly faithful to the scene of their making, so at home in their landscape, they leave the listener reeling. “Driving Around” (which, hilariously, follows “Going Nowhere,” succinctly summarizing the experience of being a queer teenager on the outskirts of Calgary), features a pedal steel line so stretched beyond its instrument that it becomes atmospheric, ambient… almost synthetic. Imprecise and unmoored, it hovers in the mix like a whisp of high-altitude cloud hanging over the prairie.

“Whatever Helps You,” in a similar turn, channels the cadence of an old-time country ballad but swaps the bouncing pluck of the standing bass for a crunchy, sharply clipped drum pad. The result is part Patsy Cline, part Billie Eilish, the two halves lashed together with a pedal steel line so languid and elastic it feels almost like satire at its own expense.

This is an improbable palette. But that it all works to such brilliant effectis a testament to Buckley’s particular gift as a songwriter: to reach into the shadowed places between worlds whose edges don’t quite line up, and find a way to call them home. As Buckley pleads on “Prairie Town Dreams,” a B-side that closes the album, “please, wide-open plains, take me home again.”

Tyler Morgenstern is a writer, communication professional, and musician currently based in Kelowna, British Columbia. His writing focuses on the intersections of culture, media, and technology. He holds a PhD in Film & Media Studies from the University of California, Santa Barbara.