Profiles in Advocacy: Karen Pittelman, Karen and the Sorrows

Editors’ Note: This is the third installment of a planned series where we profile artists and activists working to make country music a more inclusive space. Our previous installments include an interview with Black Opry’s Holly G and a profile on “Proud Radio”‘s Hunter Kelly.

by Rachel Cholst, Senior Editor

Sometimes, all it takes is for one person to show the way. New York City’s Karen Pittelman of Karen and the Sorrows is that person for the modern queer country scene. For ten years, Pittelman has organized queer country shows in New York City that have branched out into international networks of country musicians. Starting with the Gay Ole Opry, the shows have evolved into a series that is at times monthly and quarterly, mostly housed at the fabled Branded Saloon in Brooklyn’s Prospect Heights.

The first concert was magical.

“People had such an intense reaction and we’re just like, ‘oh, I’ve been waiting for this my whole life,’” she recalls. “I think that that’s still true and that’s part of why queer country music has taken off in a wider way: there’s just so many queer people who love country music, and that cognitive dissonance of loving something that doesn’t love you back is so intense that when you find a space where you can be your full self and love the music you love, it’s powerful.”

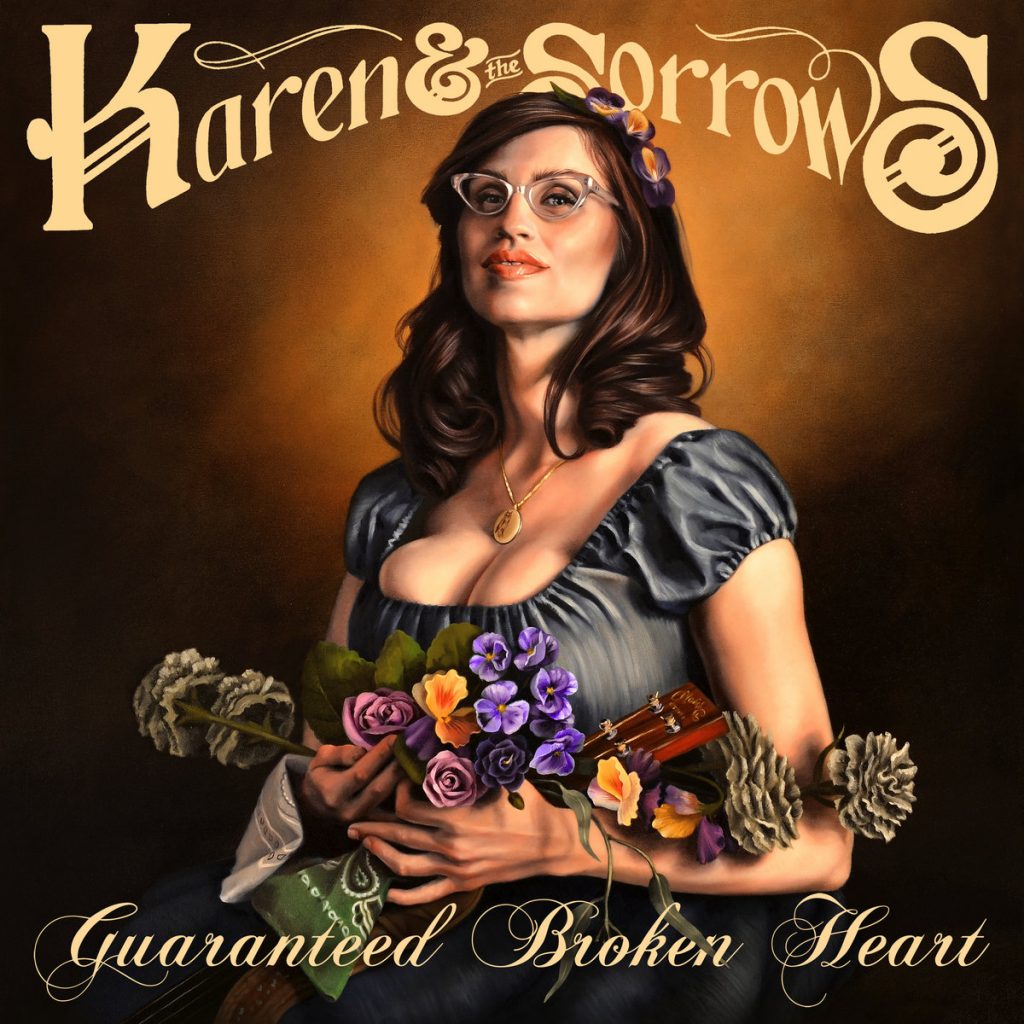

With 2019’s Guaranteed Broken Heart, Karen and the Sorrows are cementing their legacy as a band that emphatically proves that queer country musicians have a place at the table — whether Nashville wants us there or not.

Pittelman is an organizer through and through: in addition to her work in the queer country music world, she has also co-written works on privilege and philanthropy, such as Classified: How to Stop Hiding Your Privilege and Use It for Social Change with Resource Generation in 2006 and Creating Change Through Family Philanthropy with Alison Goldberg in 2007. As the queer country scene has flourished, Pittelman is taking on the broader, deeply-rooted culture of white supremacy in Nashville.

For Pittelman, all of this work is intimately entwined: she cut her teeth in the Boston queercore scene after graduating from college.

“I was super crushed out on Slamber Slessor. She was in a bunch of bands, played electric guitar and the drums. So I would say follow Slamber around to her shows. That was where I learned about building musical community. In that world, it wouldn’t make sense to separate politics from the music. They were always woven together and so much about that was like building spaces that people could feel at home.”

“And not to say that people didn’t fail,” she points out quickly. “Like, they failed all the time and they failed really astronomically. And I think a lot of failures around thinking about racism, a lot of failures in thinking about transphobia…But at the same time, people were grappling with that. It was a given that that conversation was happening, as opposed to any other music spaces.”

When Pittelman tried her hand at making queer country music, she yearned for that sense of community.

“I missed making music in a space or listening to music in a space where we were bringing our whole selves and where we were trying to create a space that felt like home and felt welcoming.”

And sometimes those spaces fail to do that: but those failures can be important.

“When you look at the characteristics of white supremacy, number one is often perfectionism. And I think that stops a lot of us from creating the kind of spaces we need because, of course, like nobody wants to fail. I don’t want to fail either! It’s terrible and nothing feels worse than realizing that you fucked up and like somebody felt bad or got hurt. But if you give up, you can’t learn from that. And the only way we’re getting anywhere is by learning and working together and being open enough to hear it when we fuck up. If there’s anything I’ve been learning as I get older, it’s getting better at failing. Being willing to hear things that are hard or feel bad, and to do your best to pick yourself back up and try again and not take it too personally.”

Overall, though, the community she has helped to foster has been a success. It began ten years ago, before social media was quite so entrenched in our daily lives. And it began the old-fashioned way: through chatting.

“We’ve just been this super grassroot community where everybody who cares about it, helps out and pitches in and runs the door and spreads the word — it’s not just about the musicians.”

Pittelman, Paisley Fields, and Wiley Gaby met through a network of mutual acquaintances in Brooklyn — all of them thinking they were the only queer country artists around. “As people come in, they bring all their energies and their strengths and their skills and then we can like create that space together. I mean, ten years went fast, right?”

These roots, of course, took more time to grow. As bands toured across the country, they took each other along, creating networks in new cities. While this may be a bit slower than liking mutuals on Instagram, Pittelman wonders aloud if it creates stronger bonds. “In the Before Times, you had to work harder to find out about stuff, and when you found something that you were really looking for, you had more of a commitment to it. I don’t know if that’s true, actually — my experience over the last ten years with this work has been, when people find us they’re so psyched.”

As queer country artists have become more accepted in certain corners of the mainstream music industry, Pittleman worries about the corporatization of the scene — much as Pride parades have been co-opted across the country.

“I’m certainly not interested in respectability politics. I come from an On Our Backs, not at off our backs tradition,” she jokes, referring to the ‘90s lesbian erotica magazine. “I want to sing about sex sometimes. Are we not queers? Do we not fuck? And country music can be really dirty! That tradition speaks to me.”

Other than musical content, Pittelman is concerned about queer artists navigating the industry itself.

“Big institutions that have no interest in really changing their power dynamics will perform diversity, but have no intention in changing; certainly no intention in confronting white supremacy or thinking about anti-racism. I certainly think that was already happening in the ways that the industry is like, ‘well, we can only talk about one thing at once. So we need to talk about women,’” she observes, referencing the disparity between women and men on country music radio.

The heart of this beast, of course, is capitalism. “Capitalism is so infinitely flexible and can find new ways to consume what we create and to assimilate it. I worry that the ways that our politics or commitment to being radical has been woven together with making this music will get torn apart.”

For Pittelman, the key to queer country music is its politics. “My project has never been for just anybody with a rainbow flag. My project has been: how do we build a space for this music that is radical and transformative so there’s a home for people who have been marginalized otherwise. So my project hasn’t been, how do we show the industry how you can make more money from us.”

Of course, people deserve to make money, too, and therein lies the rub. Overall, though, Pittleman is thrilled about the growth of queer country music.

“I feel so energized. Some people are just making the music they love and they’re called to make. And I love when people are collaborating and it takes off. I’m thinking maybe it’s time to wrap up the concert series in its 10th year, because there’s so many other things that are happening. It’s blossoming in all kinds of different ways and I don’t necessarily have to be the one to keep doing that work.”

Whatever happens with the Gay Ole Opry, Karen Pittelman’s work reforming country music is just getting started, thanks to the organization Country Music Against White Supremacy. The organization began as a call to action after the deadly violence in Charlottesville, VA. Pittelman felt the country music community should have had an organized anti-racist response to the events, rather than simply silence — especially compared to artists in other genres. Pittelman wrote the essay “Another Country” as a call to action for those who believe in country music’s power to change and reflect the real America, warts and all.

In response to this inaction, she organized several meetings — one in-person meeting at Americana Fest in 2019, some on Zoom, all the while collecting names and contact information at concerts for a mailing list that is now 200 people strong. The group has launched the Change Country Music pledge.

“So much of the ways that white supremacy plays out within these industries are through these informal networks: who they know and who they lift up. It’s often these all-white networks. So for the pledges, if you’re an engineer, you pledge engineering hours and you’re giving people free engineering time, you know, or free PR time, or playing on people’s album as a studio musician.”

In July, the organization hosted a workshop on how to pitch work to music journalists.

Whether you’re a fan, artist, or industry insider, Pittelman knows there is a place for you within country music. The queer country music, especially, has a special power.

“It helps people realize, ‘I can listen to the music that I love. And I am with people who believe my life is sacred, who are going to have my back and fight for me.’ There’s something really transformative about that when we do it right. Together we can create that communion with each other that has real power.”

Rachel Cholst is an educator, comic book writer, and music journalist in New York City. In addition to her role as Senior Editor of Country Queer, she produces the podcast and blog Adobe & Teardrops, as well as the podcast Country Queer Spotlight. You can find her on Twitter at @adobeteardrops and on Instagram @adobeandteardrops.