List: Queers & Allies, Standing Together

By Dr. Matthew J. Jones

Country music sometimes gets a bad rap as a clearing house for conservative ideologies and ant-LGBTQ+ sentiment, and that is certainly accurate in some cases. But the full truth isn’t quite so simple: country music has a long, complicated history with LGBTQ+ rights.

In her book Rednecks, Queers, and Country Music, Nadine Hubbs, Professor of Music and Women’s Studies at the University of Michigan, makes the following observation:

White working-class folk in the American hinterlands are rednecks. And rednecks are bigots and homophobes. This is common knowledge and reliable terrain for launching any number of stories, jokes, and armchair analyses.

To many folks, especially those who do not live in flyover zones or listen much to country music, such a statement has the self-evident truth of an axiom. But as Hubbs and other writers (including Shana Goldin-Perschbacher, whose dazzling new book Queer Country is worth reading), blanket condemnation of country folk as bigots, homophobes, and religious zealots upholds a certain middle-class, coastal status quo. The country-scape is far more diverse (in every sense of that term) than sweeping condemnations and dismissals allow.

Recent years have witnessed a queering of country, with out and proud artists like Chely Wright, Orville Peck, Namoli Bennett, Brandi Carlile, and Ryan Cassata joining more established figures like Billy Gilman, Ty Herndon, k.d. lang, Mary Gauthier, Gretchen Phillips, and Indigo Girls.

While these names are among the most recognizable in country music, there is a rich and varied tradition of LGBTQ+ country artists who may not be household names but whose music should be on our playlists. Historian JD Doyle has put together an invaluable resource as part of this Queer Music Heritage project, documenting queer country music for posterity. Check out Part 1 and Part 2 of Doyle’s “Gay Country Music” archive, where you can learn about Lavender Country (1973), which has been featured in these pages before, Doug Stevens & the Out Band, Glen Meadmore, David Alan Mors, Sid Spencer, and many others.

Below are a few moments when country music sang out for LGBTQ+ visibility, representation, rights, and ideals. We put together a Youtube playlist as well as a Spotify version, although the David Allan Coe song is unavailable on Spotify at this time.

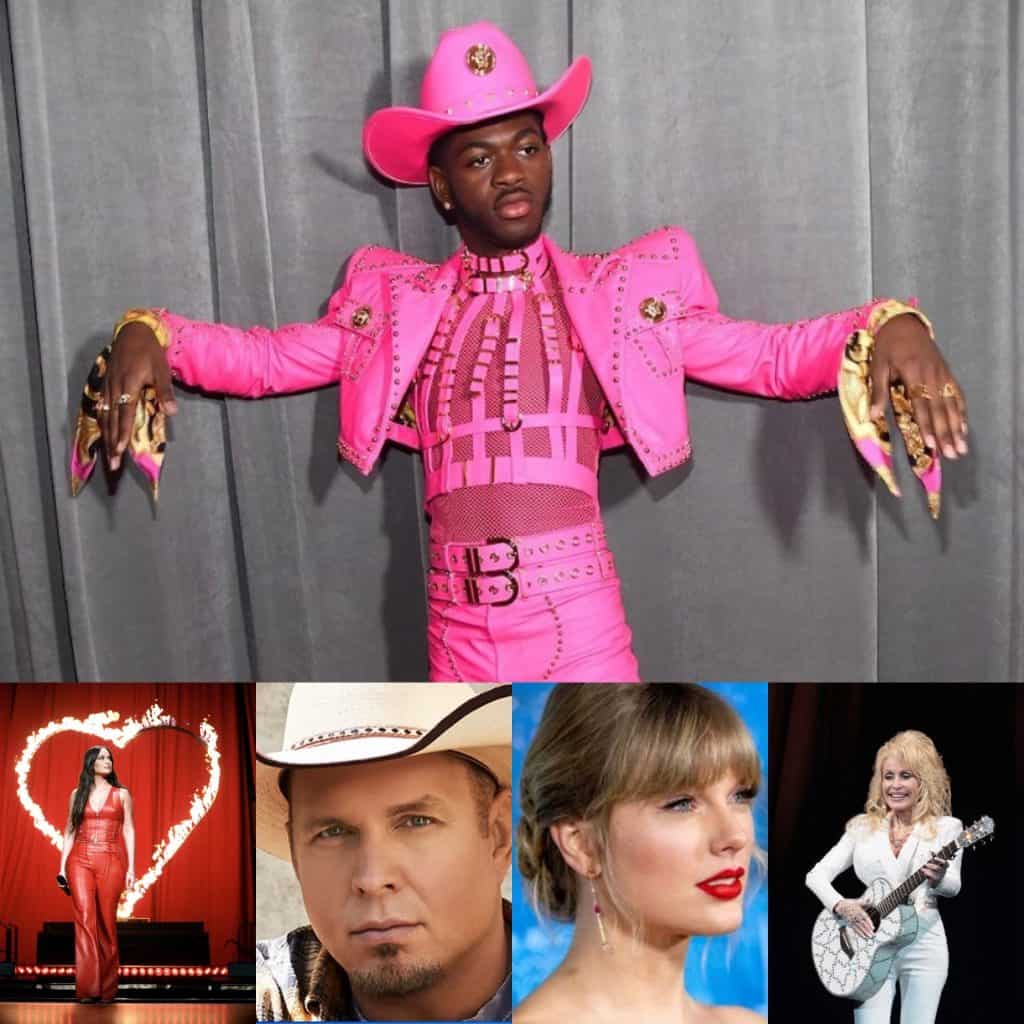

Lil Nas X (featuring Billy Ray Cyrus) – “Old Town Road” (2019)

In a few short years, Atlanta’s Lil Nas X has taken the world by storm as one of the most visible queer African American artists in popular music. His music videos (especially “Montero (Call Me By Your Name)” have raised the ire of homophobes and garnered critical acclaim from progressives. Nas first burst onto the music scene with “Old Town Road,” a country-rap song he wrote using a beat purchased from Dutch producer YoungKio and wrote in a day. Nas initially released the song via his SoundCloud account, and it became a viral sensation on TikTok, where it caught the ear of Columbia Records, who signed him in 2019. A remix featuring country legend and LGBTQ+ ally Billy Ray Cyrus came out later that year. While the African American roots of country music are often hidden in the mix (to borrow the title of Diane Pecknold’s important book), Nas and other artists of color and queer performers bring a new perspective to contemporary country music.

Kacey Musgraves – “Follow Your Arrow” (2013)

Kacey Musgraves’ debut album, Same Trailer, Different Park, introduced a new voice in country music, but one connected to a long legacy of women (like Loretta Lynn, Tammy Wynette, Kitty Wells, and Patsy Cline) who used songs to comment on topics domestic and social, personal and political, with a mixture of sincerity and sarcasm. Her debut single “Merry-Go-Round” captured the sense of longing and ennui that those of us who grew up in small towns know all too well, and the singer foregrounded LGBTQ+ allyship from the start of her career. The album’s third single, “Follow Your Arrow,” (written with queer country songwriters Brandy Clark and Shane McAnnaly) encourages listeners to dance to their own beat, whether that involves kissing lots of boys, girls, or no one at all. “When the straight and narrow gets a little too straight…just follow your arrow wherever it points.”

The Chicks – “March March” (2020)

Twenty years ago, The Chicks caused an uproar among supporters of President George W. Bush when they made comments that were critical of the war in the Middle East during a live concert. The resulting backlash threatened to derail one of the most successful careers in modern country, but Natalie Maines, MartieMaquire, and Emily Strayer stuck to their principles and weathered the storm of criticism and hatred. A few years later, they released Taking the Long Way (2006) and its single “Not Ready To Make Nice” became one of their biggest hits. In 2020, they released Gaslighter, which contained the single “March, March.” To create the video, The Chicks sought input and guidance from multiple communities, including #BlackLivesMatter and LGBTQ+ rights activists. The single showed that The Chicks remain committed to social justice and that they are willing to do the work to learn how to be strong, supportive allies.

Indigo Girls – “Country Radio” (2020)

I’m an unapologetic Indigo Girls stan. As a teenager growing up in rural Georgia (their home state, too), I used their music to rehearse experiences of longing, love, loss, and life that I hadn’t yet experienced. Committed social justice activists, Amy Ray and Emily Saliers have consistently demonstrated how artists can foreground their convictions with integrity and artistry since they first emerged in the 1980s. While many of their songs have queer content (for example, “Least Complicated”), “Country Radio” from their most recent album, Look Long, captures the way that queer kids form attachments to “objects of high or popular culture, or both, objects whose meaning seem[s] mysterious, excessive, or oblique in relation to the codes most readily available to us,” as queer theorist Eve K. Sedgwick writes in her important essay “Queer and Now.” In this case, songs pouring out of country music radio provide a way that queer listeners can endure and survive a hostile and oppressive status quo.

Taylor Swift – “You Need to Calm Down” (2019)

Ok, ok. This isn’t really one of Tay Tay’s country (or even folksy) songs, but there’s no doubt that her roots are firmly in country, and as her most recent albums, Folklore and Evermore, suggest: Taylor Swift can drop a bop in pop and turn out a gut-wrenching acoustic ballad with equal panache. On its surface, this song, from 2019’s Lover, gives Swift a chance to clap back at some of her critics and haters, but the music video offers a lesson in queer representation and visibility. Through a process that music video theorist Andrew Goodwin termed amplification, Swift and video director Drew Kirsch add new layers of meaning to the lyrics by featuring a panoply of LGBTQ+ pop culture icons living their best lives in an RV park whose pastel palette evokes San Francisco’s famous “Painted Ladies.” While religious zealots and bigots condemn queer folks, A’keria Davenport, Adam Rippon, Adore Delano, Billy Porter, Jonathan Van Ness, Laverne Cox, and Rupaul show that real power can be found in community, friendship, diversity, and chosen family.

David Allan Coe – “Fuck Anita Bryant” (1978)

I had never heard of this song until I read Hubb’s Rednecks, Queers, and Country Music, but it’s a remarkable document for its time. For those who don’t know, Anita Bryant is a former Miss Oklahoma who went on to become a singer, the spokesperson for Florida Orange Juice, and the face of anti-gay bigotry in the 1970s—the former won her a pie in the face during a now famous 1977 press conference.

Coe—whose songs “Would You Lay With Me (in a Field of Stone),” “You Never Even Call Me By My Name,” and “Take This Job and Shove It” earned him a place in country music history—released this song on an underground record in 1978. Although he uses language and clichés that may not sit comfortably with a lot of listeners today, the song’s arc-perspective and attitude toward Bryant makes it a surprisingly early pro-LGBTQ+ statement for one of country music’s outlaw figures. And Coe is not alone. Other country outlaws like Willie Nelson (who recorded the campy “Cowboys Are Frequently, Secretly Fond of Each Other” (2006) and Merle Haggard—a longtime Republican who nevertheless advocated for individual rights, spoke in support of The Chicks in 2003, and even wrote a song in support of Hillary Clinton that included the line “Change needs to be large, let’s put a woman in charge”.

Orville Peck – “Daytona Sand” (2022)

“Give a man a mask,” Oscar Wilde once quipped, “and he will tell you the truth.” Since his indie-released debut album, Pony (2019), this masked gay man has been singing his truth. With a voice that hovers somewhere between Roy Orbison and Elvis and a style that simultaneously acknowledges country music’s roots and pushes the genre forward, Peck is in the vanguard of contemporary queer country artists. While none of his songs are explicitly political, he is doing the important work of making queer country visible and making queerness visible to country audiences. In “Daytona Sand,” for example, he sings of being world-weary and lonely and finding love, or at least connection, in fleeting moments. In the music video, we see Peck dressing in a hotel room where his handsome paramour still sleeps before the singer slips off to the next gig, in the next town… the age-old cowboy/drifter motif, thoroughly queered.

Garth Brooks – “We Shall Be Free” (1992)

In the early 90s, Garth Brooks was the undisputed King of Country music. His eponymous 1989 debut and its follow up included several songs that were destined to become country classics, including “If Tomorrow Never Comes,” “The Dance,” “Friends in Low Places,” and “The Thunder Rolls.” The latter, a song written by Brooks and Pat Alger, was originally cut by Tanya Tucker but got shelved until the release of a 1995 boxed set. It addresses domestic violence, a taboo subject for country in the 1990s, and Tucker’s version includes a fourth verse in which the traumatized wife murders her violent husband, making the song a cousin of Bobby Russell’s “The Night the Lights Went Out in Georgia,” (made famous by Vicki Lawrence and, later on, Reba McEntire) and other country murder-ballads. “We Shall Be Free” is gospel-influenced prayer for peace, justice, and freedom that includes the line “When we’re free to love anyone we choose…we shall be free.” Brooks’ willingness to embrace LGBTQ+ folks decades before many country stars made such public statements is allyship in action.

Dolly Parton – “Family” (1991)

I’m glad I get to live in the same world as Dolly Parton. From the start of her career, Parton has made room for everyone, showing compassion, grace, love, and acceptance for her fans—and even her detractors. She has also been a gay icon from the start, as the legions of drag artists who have impersonated Parton over the years surely attests. She even famously showed up to participate in a Dolly look-alike contest that featured drag performers—and lost!

More recently, she produced the film Dumplin which features a Dolly-themed drag show, and contributed songs to the movie’s soundtrack. Parton has embraced her LGBTQ+ fans for decades, telling the media that “if you’re gay, you’re gay. If you’re straight, you’re straight. And you should be allowed to be how you are and who you are.” In 1991, she included the song “Family” on her album Like an Eagle When She Flies. Although it’s something of a deep cut, it’s worth checking out. “Some are preachers, some are gay, some are addicts, drunks, and strays. But not a one is turned away when it’s family.”

Thank God for Dolly Parton.

Matthew J. Jones is a queer musicologist, writer, performer, Joni Mitchell fanatic, and assistant professor of musicology at Oklahoma City University. He lives in Oklahoma City with his cat, Ouiser.