The Faces of Paula Boggs

By Abel Muñoz

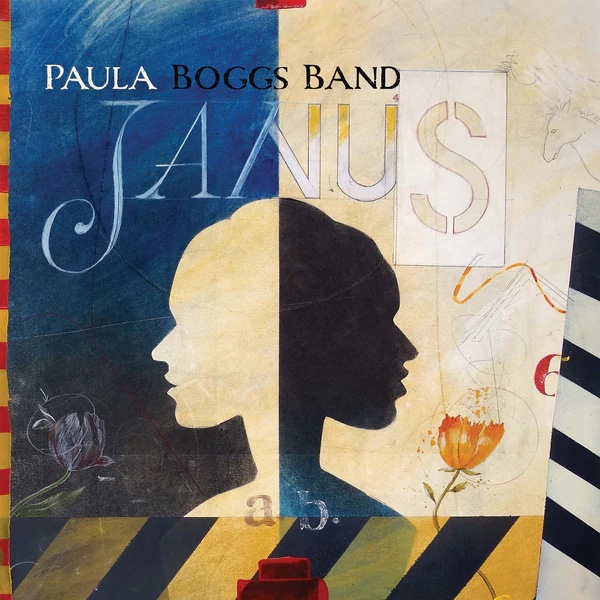

Ahead the release of Janus, the new album from the Paula Boggs Band, I had the good fortune to chat with the band’s lead singer and songwriter, Paula Boggs herself. The band’s signature sound, an amalgam of bluegrass, jazz, Americana and r’n’b that they call “soulgrass,” mirrors the multiple lives Boggs has lived. Boggs has made her mark as a musician, a speaker, a writer, a lawyer, and a philanthropist.

We talked about some of her influences before diving into the story behind Janus, out on April 1st.

Could you tell me a little bit about some of your influences in general, and on your new album in particular?

I think there are a number of chapters for my influences because I started playing guitar and writing music as a 10-year-old. I was a Black Roman Catholic in the segregated South as the church was embracing folk music. As I was learning guitar, I was also learning songs like “Sounds of Silence.“

My dad was Catholic, but my mom was African Methodist Episcopal (AME), and they were playing and singing gospel and spirituals. Folk music and gospel music are the music of roots. And so even though at first blush, they may seem different in some ways, they come from the same place. They come from the earth. So that music still informs the music I write.

A big change happened when my mom took her four kids out of the segregated South to Europe. I discovered jazz there. Europe had a lot of expat American musicians who tended to be either jazz or classical musicians. And so those people and their sounds rubbed off on me.

“Shadow of Old Glory,” a song from the new album, is very Baroque. There’s a vibe and the story in the song is very Baroque. Coming back to the United States, a lot of the music that I think my peers were listening to as teens, I wasn’t.

The punk scene of the seventies kind of escaped me except for the EDM precursor piece of that like, the German electronic band Kraftwerk. I spent three years in Berkeley, California and most people had discovered music I was discovering for the first time. The music of Jefferson Airplane and Grateful Dead shaped the San Francisco Sound.

How has Seattle influenced your sound?

I think Seattle has had a major influence on my life outlook. The physical story found in my songs for the most part is Seattle. There are songs that are sort of situated in other places, but most of the songs I write are coming from a prism of this place. This place of immense physical beauty. I sometimes say Seattle is a magnet for people who draw outside the lines.

Seattle is marked by innovators in music, in the sciences, in all art forms. People aren’t gonna tell you, “You can’t do this.” That’s not Seattle. Creating something called “Seattle Brewed Soulgrass” is very much at home in the sort of Seattle ethos. It’s something that often defies label and characterization,

I don’t think we give enough credit to geography when we think about the arts.

Many years ago, I happened to meet a diplomat from Spain. We were talking about the similarities between Seattle and some of Spain’s coastal cities. And he made the observation that coastal cities tend to be the more liberal and progressive because you are literally looking outward.

Let’s talk about your new album. You named it Janus, which references the god of looking in and looking out. How do you think that this album captures that idea?

I don’t know if I would’ve come up with the name Janus. I wrote most of this album during a time I call the triple pandemic: a pandemic related to public health, a pandemic related to race and a pandemic related to politics. In a couple cases, I reimagined songs that I had written before or earlier. They became something different. I can’t divorce what this album is from the time we’re living in. And, and part of that is due to the unprecedented isolation of these pandemics. I had to spend time with myself in ways that for better or for worse I haven’t really in my entire adult life. That introspection led me to asking fundamental questions. Like, when did my family get here? And what can I learn? Globally, we are known as a nation of immigrants, but we’re not. We’re a nation, mostly of immigrants, but there are three legs to that stool. I mean you’ve got the immigrants; you’ve got the indigenous and you have the enslaved and their progeny. So that really forced me to kind of say, okay, what is this country? What is my place and what do I wanna say about it?

And of course, you know, some of my writing was happening in the immediate aftermath of George Floyd’s murder. It wasn’t just about ancestry but that line between ancestry and today. The fusion of these three pandemics as I’ve described them really for me became my paintbrush for the songs that appear on Janus.

“King Brewster,” your lead single with Dom Flemons, discusses the line between ancestry and the present. Why do you think we need this song today?

There was an African American female professor I read around the time I was thinking about writing “King Brewster.” This professor wrote an article where she basically said the story of America is in my face, physically on my face. Means that most African Americans are about 20% white or more.

It’s too trite to say that, well, there are these white people and there are these Black people because you know, most Black people in the United States have white in them.

That led me to discover King Brewster, the child of a slave owner and a slave. And so its relevance today pertains to the difficulty we have reconciling the truth about race and this country. And I think part of the answer is getting us to have honest conversations around who we are as a people. I’ve always believed that music is a very feeling medium. People are often able to receive information musically, that they’d never be able to through spoken word.

In the song “Ebony Revisited,” one of the lyrics says “this is not my home.” What does home mean to you as Black woman, as a queer woman, as a queer Black woman?

“Ebony Revisited” is one of two songs on Janus that I started writing as a very young adult and then just sort of abandoned. When I first started writing this song, I was interning in Washington, DC, the city of my birth, but I didn’t know anything about this place at that time.

There is a tension between this traditional view of home, where you were born, and what you choose to be your home. There are times when within a chosen community, but I don’t necessarily feel at home. There’s an alien quality to it. That’s beyond geography. There are times when I feel alien within the African American community. There are times when I feel alien within the LGBTQ community. There are times when I feel alien within the veteran’s community. That’s why Seattle as a place has always felt so good to me, because I didn’t really have to choose.

Your next single, “Motel 6, Serenade,” seems to encapsulate the idea of looking forward and looking back at the same time. Could you tell me why you selected this one as your next single?

I’ll be perfectly honest with you; it wasn’t my idea. I was kind of talked into it because sometimes it takes an objective ear to help an artist know how a piece of art will be received. Some people just respond to the musicality of it. It’s an interesting showcase for what we do as a “soul grass band,” because it is probably the most rock influenced song on the album, but it ends in banjo. It takes the listener on an interesting journey. Rhythmically it has this sort of, you know, Beatlesque Sergeant Pepper-era feel to it. But the story is more universal than I thought. I was expecting people my age and generation to have a response of nostalgia, but I’ve had people in their twenties say to me, “I love that song. It reminds me of high school.”

Thank you!

Thanks for having me.

Abel Muñoz (He/Him/His) is originally from Texas and now lives in Nashville. He is passionate about art, but most days he can be found working at a sexual health clinic. He loves 90s country music, especially Linda Ronstandt and George Strait. His ramblings and adventures can be found on various social media platforms (Twitter: @artofspectator, IG: @artofthespectator).