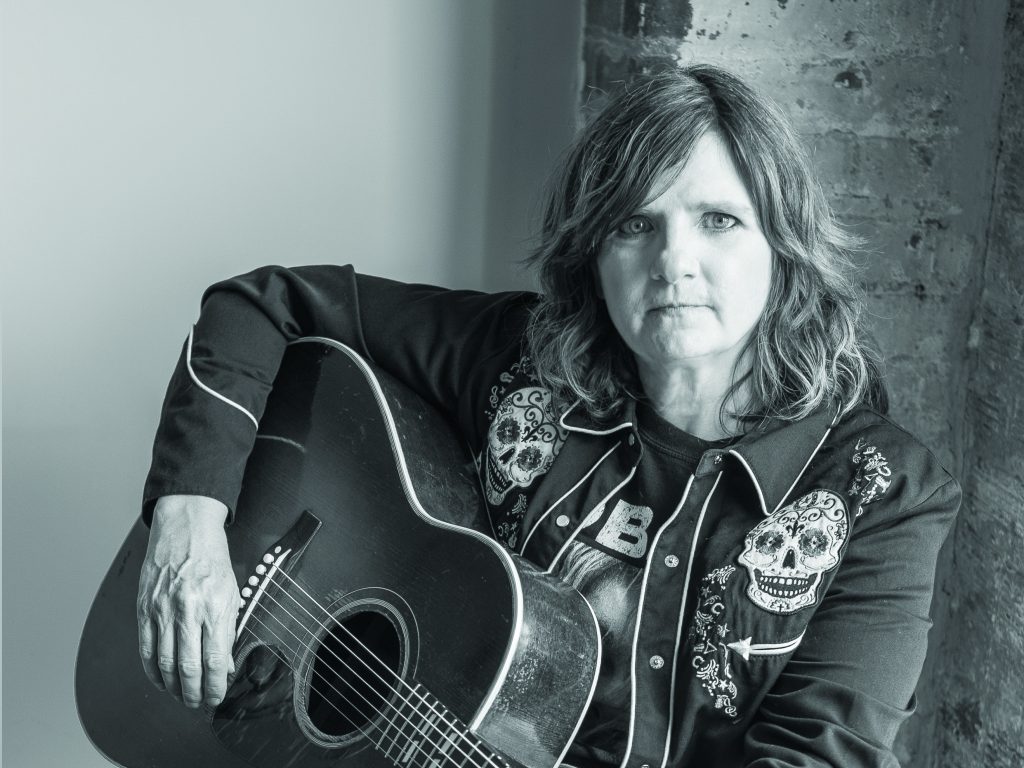

Amy Ray’s Queer Country Story

By Abigail Covington, Contributing Writer

When you look at the current slate of queer country artists, you might like what you see. Out artists like Amythyst Kiah, Orville Peck, Justin Hiltner, Brandi Carlile, Brittany Howard, and Mercy Bell have garnered praise from the media and attracted large audiences, with or without institutional support. There is still much work to be done, but for those of us who grew up during Chely Wright’s closeted “Single White Female” era, queer country’s current roster is a beautiful sight.

Of course, none of the aforementioned artists’ success would be possible without the hard work done by those who came before them. One particularly hard working group is the Indigo Girls. Comprising lifelong friends Amy Ray and Emily Saliers, the Indigo Girls have been one of folk rock’s iconic groups for over three decades. While the duo’s crisp harmonies and sweeping lyricism have won them multiple accolades over the years, perhaps equally important to their legacy is their history of activism, fighting for LGBTQ and civil rights in their native state of Georgia.

Country Queer caught up with Amy Ray recently to get her take on all the things queer country artists have accomplished and how far the scene still has to go. When we got hold of Ray she was quarantining in her house in the mountains of Georgia, where she has lived for the better part of her life.

You made a fateful choice to stay in the South as opposed to moving somewhere more LGBTQ-friendly. What was behind that?

I don’t know what I would do in a place like New York where it’s not a challenge all the time. I’m so used to an uphill battle and rubbing against that and getting energy from it and trying to change things. And I love where I live. I don’t want to not be able to live in a rural area because of laws and weird bigotry and racism and homophobia. I’d feel differently if I was black because you can’t hide. Racism is so much harder to beat than homophobia. I have the privilege of living in a rural area and being white and still having somewhat of a way of navigating things without risking my life.

Do you think you would feel the same if you were a gay man?

I think it’s really hard to be a gay man in America. Having said that, my friend Frank and his boyfriend live 20 minutes from me in Dahlonega [Georgia] and he has lived here forever — for 40 years. He knows everybody in town and he just basically takes the high road all the time. He assumes the best about people. He’s amazing. And everyone loves him and he’s a gay man. But he goes to the Unitarian church and it’s been vandalized a lot. There’s a lot of people that do not like gay people where I live. A lot, like a majority. But he’s an example of someone who is gay and has figured out a way to navigate it. He isn’t going to leave.

Going back to what you said about how you derive energy from having to climb an uphill battle: how do you think you would feel as an artist today when it’s so much easier to be out than it was even 10 years ago?

The reality is there’s still so many places where it’s not easy. Where I live, it’s a big deal to come out. Kids are still committing suicide because their parents throw them out of the house because they’re gay. We’ve progressed in circles of entitlement, but we’re still fighting so many battles, you know? I don’t think I would come up during this time and be like, “Oh, I have it easy.” I think I’d still have an eye towards the underdog in other places. The underdog might not be me as much, but that’s my perspective. It’s the lens I see things through. It’s just the way I came up.

Why do you see the world that way? Why focus on the underdog?

[Laughs.] I don’t know! Exposure to music from the ‘60s maybe. When I was a kid, I was obsessed with Native Americans and what happened to them and why. I was constantly co-opting that fight. I wanted to be the Native American in the Thanksgiving play and things like that. I don’t know why or where that came from. If I came up today, I think it would be easier in some ways to be gay, but we’re not far enough along where it would just be like, “Oh, this is a piece of cake.”

There is still so much sexism and homophobia in the industry. And even in the pop world, maybe the audience doesn’t care if someone’s gay, but the gatekeepers are not that different than they used to be. People like Billie Eilish do really well, which is great, because I’m a huge fan. But the gate is still closed to a lot of people. I still have young artists say to me, “How do you think I should handle the fact that I’m gay?”

And I’m always like “That’s a bummer that you feel that way, and you’re only 20 years old.” But it’s the world they are coming from. It’s still real to them. They don’t want to get pigeonholed.

Do you think that being gay inhibited the Indigo Girls’ ability to have mass appeal?

The industry when we were coming up was definitely homophobic. There was more sexism than anything else. People said to us, “You guys don’t fit the mold of women.” So it wasn’t just about sexuality, it was about gender too and our presentation. I think that women, when we were coming up we’re supposed to be a certain thing and it was hard to break that mold.

It’s hard to know what would have happened. Maybe it took us a while to get great at our craft too. I can’t judge my own music. I don’t know if it should’ve had mass appeal. But what I do know is that a lot of doors seem to be closed to us because of the way we presented as women and our sexuality. We endured a lot of bad jokes from radio programmers. We heard later on things like “Well, we didn’t want them to be in any gay publications so we didn’t let them do the gay interviews” early in our career.

When I was younger and read reviews, they would mostly be about who was in the audience, not about the music we were making. They would be dismissive of the audience, because it was a lot of women, not even gay women, just women. Critics said we were mediocre and had given rise to mediocre folk music by other people as well. That was our legacy. It wasn’t good music criticism. I love good music journalism. I will read good music writers and even if it’s about me, I will take it in and take it to heart. But there’s a lot of people out there that are just misogynist, and I don’t even take it seriously now.

So yes, I know we were held back and it limited our potential, exposure, accolades, or whatever. But I also can’t be a judge of our own skills and whether the songs were good enough. All I know is that we’ve endured. And I’m thankful for that.

What about the concept of relatability? How do you think that ties into having mass appeal?

The reason why queer audiences are attracted to queer singers and bands is because they’re singing and writing about their life. But when I was young and heard bands that I liked like Jackson Browne, or the Clash, or Patti Smith, I wasn’t thinking, like, “Oh, they’re straight. I can’t relate to this.” I was thinking “I’m in that song!” because gay people are so used to having to put themselves into straight songs and translate it to work for their lives. It’s an innate ability for us.

That’s fucked up!

It is fucked up! And it’s not going to change until all these kids that are coming up now that are six years old, who don’t care, who really see things so differently than us, grow up and make music.

I can’t help but think how limiting is to not have your music be considered “relatable” to 90% of the world.

Yeah, but remember that people are being told what they can relate to as well. If you take away the way playlists are programmed, and the editorialization of what people are presented with, I think you’d be surprised at what some straight people could relate to. And they would be surprised. This is not just us being conditioned from the past. We are still being conditioned by Spotify and Pandora playlists. By what we hear in the grocery store. It’s so systemic that undoing it is…I don’t even try. I just say, “Let’s just do our thing, because eventually this will be undone because that is progress. We will evolve and the dinosaurs will die.” They’re already obsolete and that’s why they’re so scared. But they have to completely die and not have the money and the power and the stock market and be the CEOs. It’s the whole corporate structure. It trickles down to art being the way that it is.

I also think some queer artists need to just celebrate who our audiences are and be proud of it too, so that we aren’t being internally homophobic against our audience because we want that other thing. I mean, why do we want it?

Because it’s more? Because it’s bigger? Because it’s considered more acceptable? Like, what is it about us that looks at that broad appeal and thinks it’s a good thing? Maybe we should be more punk rock about it and say, “I don’t want to appeal to a broad audience! I want to be special. I want to be curated by people that I respect, which is the punk rock queer crowd!” We could turn it around.

What do you think about the increased efforts to talk about queer country music and queer Americana music?

I think the scene has changed. And I think we’ve come a long way in some ways but not in every way. There’s not enough representation of people of color in country music. There’s enough people playing it, but there’s not enough people talking about it. White guys still run the industry. It’s so systemic. The Americana association can say, “We’re going to give an award to a black person this year at the AMAs” but it’s not just about that. Every individual within the system of Americana music has to work on this as an individual. You have to build an infrastructure and a business plan that is more inclusive of communities and artists of color. And you have to acknowledge that it’s going to take years to do this work.

Who is being left out of Americana and country music’s new, albeit tepid, embrace of queer artists? Where is the support for the flamboyant male country singer? Or the butch woman? Or the trans artist?

Well, Terry Clark is a butch woman and she made it. But she had to really play up to this butch woman character who good old boys love — like a badass in a feminine and kind of closeted way as well.

So in order to make it, you really had to be a trope. So, if you’re going to be butch you can’t be…

You can’t be political. You can be butch, but you can’t be political. You can be political if you’re femme. You can only have a certain number of things going on at any given time. So if you’re talking about me, forget it. I’m over 50, I’m political, I’m butch …

Did the Indigo Girls ever try and break through in Nashville?

We were dissuaded from trying to break into Nashville early on by people around us who felt like it was too prohibitive for us because we’re so politically left as performers, not just as songwriters. But I always felt like we had a thread of country in our music. We were influenced by people like Neil Young and Lynyrd Skynyrd.

You were influenced by Lynyrd Skynyrd?

[Laughs.] I can’t help it. I was a redneck in high school. I didn’t know what I was doing. I had a lot to learn. I had two sides. I was very oriented towards the Woodstock generation and peace and anti-racism. But the other half of me was listening to “Sweet Home Alabama.” Emily has a fascination with pop country. We were big Dixie Chicks fans. They were at Lilith Fair and we got to be friends. But I was always more into what’s considered Americana now – Steve Earle, Lucinda Williams, even Johnny Cash, even though he’s considered country.