Tiger King’s Country: The Flawed Representation We Need?

By James Barker, Contributing Writer

“Tiger King,” the surprise Netflix hit during this Covid-19 pandemic, is flawed in many, many ways. Its representation of southern LGBTQ lives and country music leaves a lot to be desired, but the documentary may have just sown the seeds for something better.

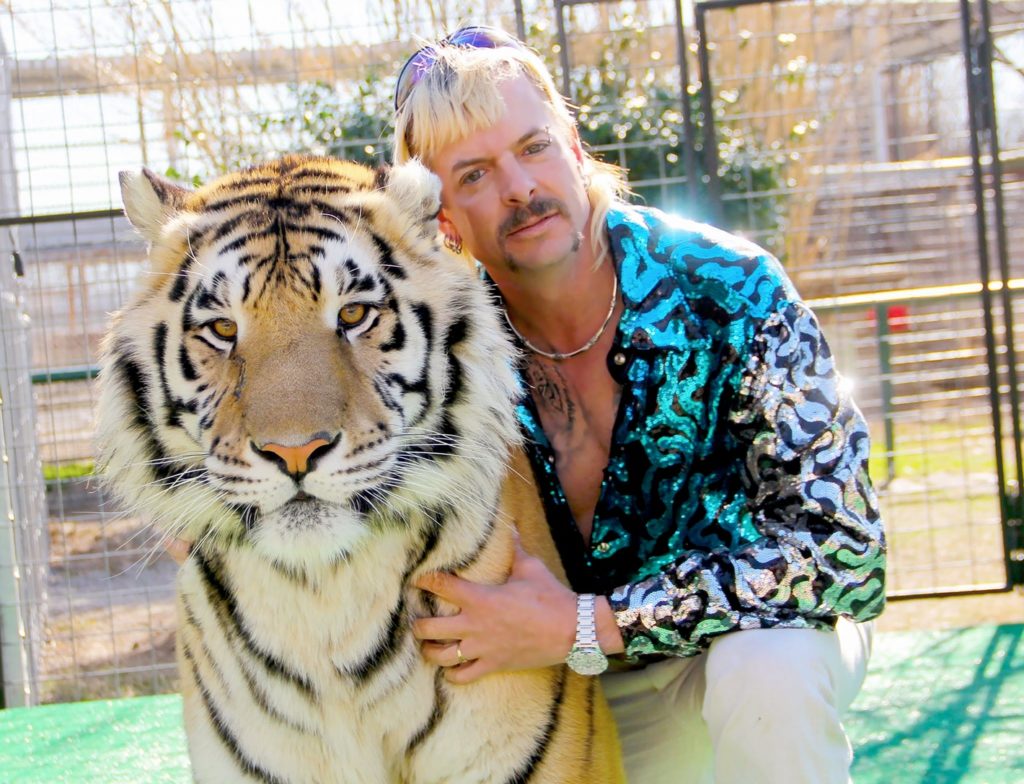

“Tiger King” makes a spectacle out of Joe Exotic using caricatures of the South, most notably its associations with depravity and sexual deviancy. The “redneck, gun-toting, mullet-sporting, tiger-tackling, gay polygamist” – and at times, country singer – is a combination that has proved to be marketable because of its outrageousness.

The stereotypes and images invoked by the documentary are also stereotypes of country music. Country music plays a subtle, yet significant, role in the documentary, and is often heard in the background during moments designed for us to sympathize with Joe. The music videos (starring Joe Exotic – but as pointed out by Sam Adams in Slate, most of the singing is not actually by him) are used to further the outrageousness of the “Tiger King”.

Joe Exotic himself trades off these images in a way that benefits his own star power, leaving other (and more diverse) representations of LGBTQ people in the shadows and having to battle with these limiting stereotypes. There have been some excellent articles, such as John Howard’s illuminating piece in History News Network about the particular issues and experiences of LGBTQ Southerners, that highlight poverty, disability and discrimination as key issues underpinning their lives; but in this documentary, these issues never get explored beyond background context.

However, the fact that “Tiger King” has cut through into the mainstream in the way that it has, means that there is potential here for a wider, more productive conversation about the biases and blind spots within national and international LGBTQ politics, especially around the South, and, by extension, about country music.

As much as Joe Exotic’s songs are about creating a larger than life persona, they strike many a familiar country music chord. Tropes of southern excess and depravity run through “Here Kitty Kitty”, which features a Carole Baskin look-alike recreating the story of her feeding her ex-husband to the tigers. Yet this is only a touch more over-the-top than a Carrie Underwood murder ballad. This song may not realistically represent everyday life, but it fits into an established mode of country storytelling.

Unpacking these conventions is key to properly understanding country music, rather than relying on surface level assumptions erasing both lived experiences and musical histories. John Howard makes a great point that the place of guns in southern LGBTQ lives is not an anomaly but part of a (dangerous) logic of protection and survival within a context of discrimination and queerphobic violence.

Joe Exotic’s use of guns in his music videos (such as the “empowering” “Bring it On”) represent a similar bind. Guns represent a tool of survival as well as functioning as a wider symbol of individualism. This dynamic plays out in country music more generally and perhaps most notably in Miranda Lambert’s “NRA gun-toting feminism” persona and in songs like “Gunpowder & Lead”, where bearing arms becomes the tool of protection against abuse, in a world with seemingly few other options.

This is not to defend or glamorize guns, or to romanticize either Joe Exotic or Miranda Lambert’s images any more than these individuals already do, but to properly contextualize them. Scratch below the surface and this may be an opportunity to address wider LGBTQ experiences of vulnerability, poverty and discrimination. Yet as things stand, southern LGBTQ people of color, trans people and LGBTQ women are left out of the picture.

Yet the country music in Tiger King has a very important function. Songs like “I Saw A Tiger” (a big and bombastic anthem that Garth Brooks might almost be jealous of) and the beautifully poignant “This Old Town,” are catchy, sentimental and ground the documentary in some sense of feeling. These songs help us believe, even if just for a fleeting moment and amongst all the outlandish content of the documentary, that we can understand and relate to Joe on a human level.

This is not to downplay any of Joe Exotic’s faults, both criminal and otherwise, but to say that this incredibly flawed documentary, “Tiger King,” may open the door to seeing what country music might have to add to discussions of LGBTQ politics. That Joe Exotic in many ways is such an awful LGBTQ representation and is in no way a positive role model may be what we need as an antidote to recent developments of respectability politics.

Joe Exotic is deeply flawed because of who he is as an individual, yet he, as much as any of us, deserves to be free from discrimination based on his sexual orientation. “Tiger King’s” only really valuable contribution is the hope that LGBTQ acceptance and equality will not be conditional on being a good or decent person, but based solely on the virtue of being human.