The Case of the Missing Trans Country Artists

Country and Americana: Y’all Got a Trans Problem

By Mya Byrne, Contributing Writer

When CQ’s editor Dale Henry Geist asked me to do a roundup piece highlighting a few, “say, five,” trans folks visible in country and Americana, I couldn’t think of five. Neither could he. We immediately understood that this illuminated a systemic problem in country and Americana: trans representation was…simply missing.

Don’t get me wrong: there are a number of excellent trans artists working in country, Americana, and folk. People like Namoli Brennet, Ryan Cassata, Cidny Bullens, and more. In tomorrow’s issue of Country Queer, I’ll introduce you to them in more depth. But with the exception of Bullens, who is about to release an album on a subsidiary of BMI, there aren’t any trans people in our genre who are skirting the mainstream or attached to major labels.

The fact is, most trans folks don’t perceive avenues for themselves in country and Americana; hence the lack of representation. There are glimpses of hope in mainstream pop music (Kim Petras), punk and rock (Mal Blum, Against Me!), and in hip-hop, R&B, and electronic music (quite notably with the amazing Mykki Blanco.) But country and Americana seem singularly closed off to trans folks. Which causes frustration, at the very least, and career dead-ends at the most.

“But wait!,” I hear in the distance. “What about Trixie Mattel?”

Hey friends, I adore Trixie, but she’s the drag persona of Brian Firkus, who is a gay man. Has Trixie brought more attention to genderfucking in country? To queer folks in country? Helped a wider audience find out about our dear living gay fairy godmother, Patrick Haggerty of Lavender Country? You betcha.

But, though I love drag and I know many trans people who do drag, drag is not trans. In fact, we trans folks, especially those of us who lean transfeminine, have been fighting for years against the tendency to conflate drag with being trans.

To be clear: Trixie’s visibility is great, but it isn’t trans visibility. Trixie’s story simply isn’t a trans story.

Our stories have a realness that is embedded in the very idea of country, which is why so many trans artists are drawn to country to express themselves, even if we aren’t getting the recognition we deserve. And our stories are what make us relevant.

Here’s what CQ pal and New West recording artist Aaron Lee Tasjan had to say about it: “There’s such a rich tapestry of life within trans lives. It feels like country music makes me feel when I listen to it. These stories are sometimes really specific, but they’re relatable stories. I don’t think that the stories are limited to the community of the artists that are creating them. They’re really powerful stories, you know? And that’s what country music is: powerful stories.”

Powerful indeed. It was good to hear that from one of the strongest allies of trans folks in Nashville. (Aaron is actively seeking out a diversity of voices to highlight during his segments on The Buddy & Jim Radio Show, broadcast on SiriusXM’s Outlaw Country station.)

My Story

Yet, as a butch-leaning trans dyke in country/Americana, I honestly don’t know many others like me. I don’t really have any “possibility models,” to use Laverne Cox’s term. I mean, I’d love to be hanging with and opening for artists like Mary Gauthier and Lucinda Williams. Our music fits together; we’re on playlists together. But it seems, and I’ve been told as much, that the industry isn’t prepared for someone like me.

My own experience navigating this world has been mixed. When I came out in 2014, I did everything in my power to make sure my album and story would be heard by those in the country/Americana scene. Over the period of a year, my friend Annie Reuter, a fantastic Nashville writer, pitched my story to multiple country/Americana publications. They all left it on the table.

New York periodicals that used to routinely cover me pre-transition—I’d even been named one of New York’s most promising artists by The Aquarian two months before I came out—didn’t respond to any of my requests for press after I came out, and didn’t list a single show from that point on.

It’s true that since then, I have landed on official Spotify playlists, been listed among peers on various queer music sites, and Aaron has even spun my song “April Fool” on his radio show. But the overall lack of coverage has remained frustrating.

I cite my experience to illustrate what I’ve had to deal with over the last six years, as someone who had a career in Americana before transitioning. I have also been blessed to be featured on three of the most well-received queer country records released since 2019 as a side person, including a writing credit on Paisley Fields’ new record, Electric Park Ballroom. Don’t get me wrong: that’s exciting! Yet in my experience, trans artists are pigeonholed for the work they put out under their own name, or simply relegated to the sidelines.

I tell myself to have patience. After all, as one of my trans friends has noted, when you transition, the metrics change. I have nothing to measure success against. Every trans artist out there, across all media, has created their own path, their own way. And the visibility we’ve managed to accomplish has been almost entirely of our own creation.

But overall, the recognition from the mainstream Americana and country world that trans artists deserve—it isn’t there.

I’m intent on changing that, and that’s why I have so much hope for Cidny Bullens’ upcoming album. I have no doubt that his profile and history–and his presence in Nashville and on a major label–will help open doors for all of us.

But I also believe that perhaps almost two decades ago, those doors could have been opened by a certain stilled voice.

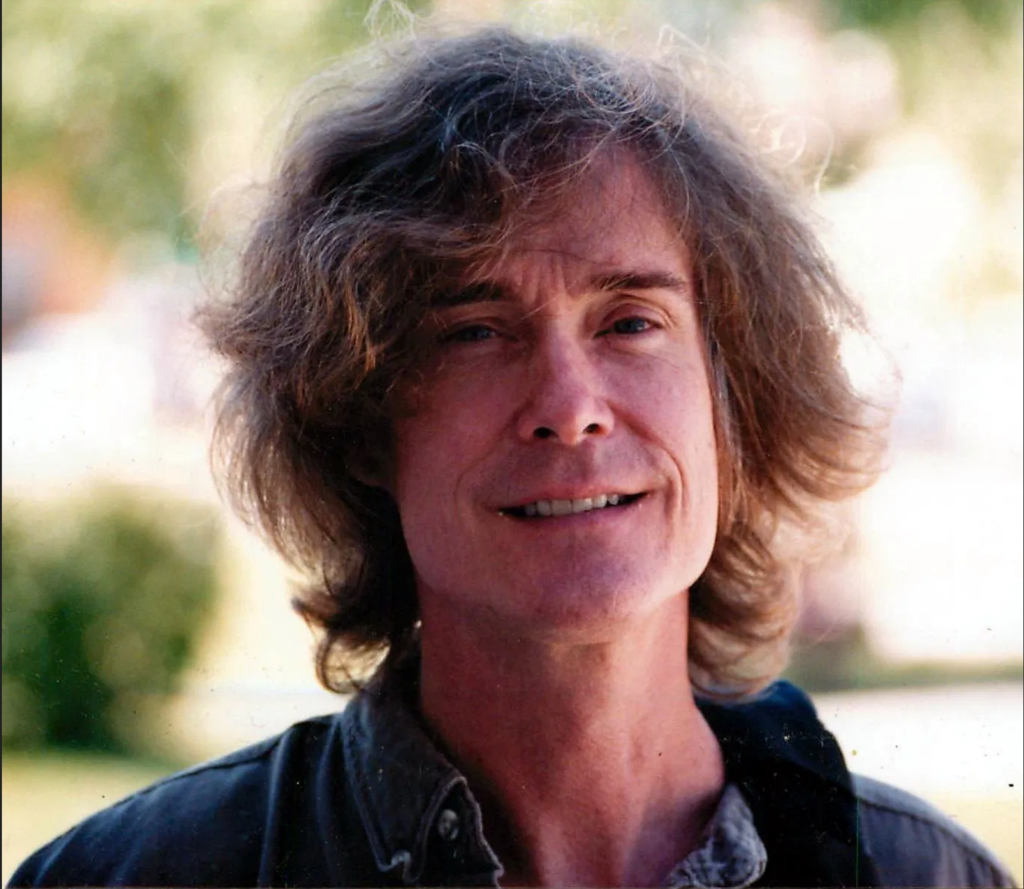

Dave Carter’s Story

I’ve written about Dave Carter* before, a fast-rising star in the folk-Americana world who was privately transitioning before a fatal heart attack in July 2002. Had Carter been able to come out as planned, I believe that would have paved the way for trans folks who work in the nexus of Americana and country.

Carter was one of the most respected folk/Americana songwriters of the modern era, covered by Judy Collins/Willie Nelson, and also Joan Baez, who compared Carter to Dylan. Carter’s transition had support from the legendary Baez, to whom Carter confided while they were on tour together. Carter’s early death was a blow, as is the fact that we’ll likely never be able to publicly affirm Carter’s chosen name, a guarded secret to very few. Yet Carter’s music has entered the American songbook, with tunes like “Gentle Arms of Eden” even featured in Universalist hymnals!

I’m Monday morning quarterbacking a bit here, but I think that had Carter lived, the industry would have shifted in the mid-2000s. There would have been no way for Carter’s transition to be ignored. I think many trans artists working in country, folk, and Americana would have found ourselves in very different positions in our careers – and indeed in our lives – than we do now. Perhaps I wouldn’t have felt forced to spend my formative career years in the closet trying to fit into a heteronormative world, denying my transness.

The Big Shift

But that’s all conjecture.

Where we are now is a world where the few trans folks who have gotten a modicum of recognition in our genre are white and overwhelmingly male. That’s a shame, as BIPOC representation is rare enough in the country/Americana mainstream, let alone adding the Q, T and non-male to that.

Americana and country require a systemic overhaul. In our conversation, Aaron Lee Tasjan weighed in: “I’m not trying to be critical of Americana, because I think their hearts are very much in the right place. They’re trying really hard to do the right things and to be diverse, but there’s so much work to be done here, and it’s going to take a long time. It’s not going to be the kind of work that has a short-term solution. It requires a lot of self-work. One way that we can change things is to plant seeds with other people. If you can have a conversation where at the end, they’re saying, ‘Oh, well, I hadn’t really thought of it like that,’ that’s really cool.”

Acknowledgment – and these types of discussions – are the first steps toward true representation. It’s time for trans folks to be celebrated within country and Americana. It’s time to create avenues for every kind of trans person. Not just because it’s the right thing to do, but because trans folks are damn good at what we do. We have a lot to bring to the party and great stories to tell. And if we don’t start building these roads, too many great stories will be lost along the way.

*Note on grammar: I don’t use pronouns when referring to Dave Carter in print. It’s been disputed as to how to accurately refer to a person who did not have the chance to come out publicly in life. Personally, following the lead of friends who knew Carter, I feel using she/hers would likely be most appropriate. However, as we don’t know how Carter would have come out—though we do know that Carter was transitioning, and was going to come out sometime after completing a busy 2002 festival schedule—in this piece, I’ve chosen to leave pronouns out completely. Why not use they/them? Well, although I often follow the convention of using singular they as a general pronoun in specific grammatical situations, I don’t believe that when writing about trans people whose gender is unknown we should automatically default to singular they, mainly out of respect for those whom they/them/theirs is their defined pronoun. But in my heart? Carter is she. As the trans essayist Elizabeth Sandifer writes in her very poignant piece analyzing Carter’s transness: “…We know she didn’t want to be a man…the use of she/hers pronouns is not the whole story…they’re just the kindest option.”

One thought on “The Case of the Missing Trans Country Artists”

Comments are closed.