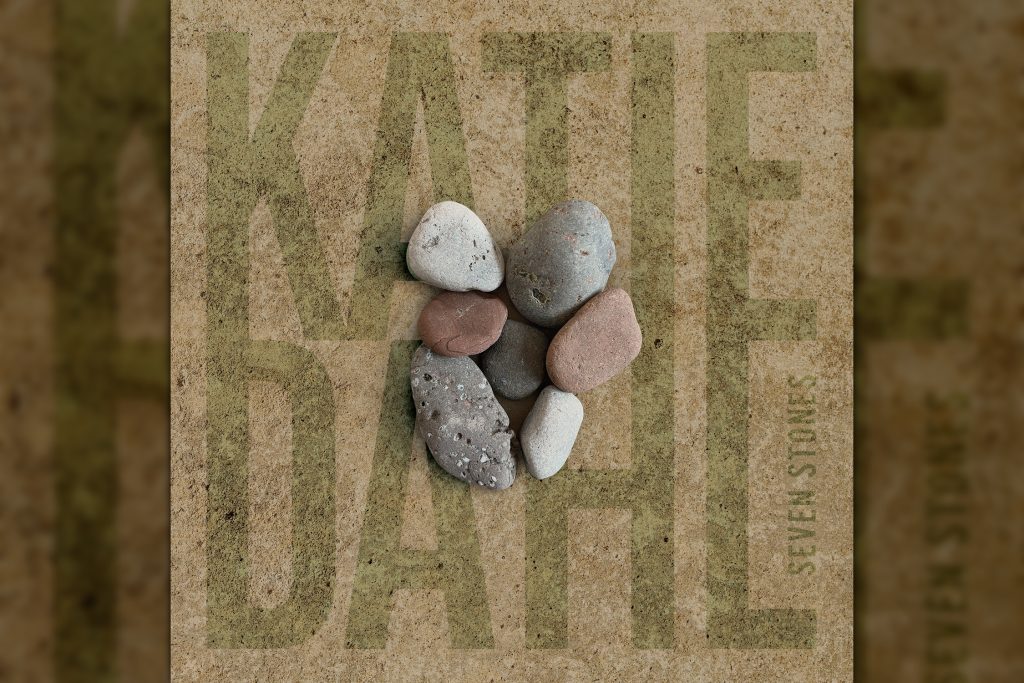

How to be Both: Katie Dahl’s Seven Stones

By Mike Fischer

What’s breathtaking about Seven Stones, the recently released Katie Dahl album, begins before one even listens to the first track, aptly titled “Both Doors Open.”

Dahl’s art design – each page split down the middle, with lyrics for each song continued across all of the pages and set at different angles and in different positions on each of them – graphically captures both the opportunity and the potential harm that comes from acknowledging the multiple pieces and fault lines comprising a self, cobbled together from the fragments that we desperately seek to connect.

Dahl’s design is also a nod to the many forms of undressing enfolded in these painstakingly honest songs – and to the challenge, once we’re invited as listeners to view such a vulnerable and exposed self, to do the requisite work that’s involved in reading the truth of what we see and hear, even when it’s presented slant.

None of which can fully prepare one for the songs to come, beginning with “Both Doors Open”: Dahl’s arresting – and musically restless – presentation of the disconnect between what we’re “supposed” to be and who we truly are, when we leave both doors open and are honest with ourselves about what we want and need.

Many of these songs suggest that (re)discovering that truth involves recovering a childlike innocence and openness to the world; they channel Dahl’s trademark nostalgia for a simpler, bygone moment. It’s a world where love – while never exactly uncomplicated – is nevertheless simpler; it exists on Seven Stones in the hope-flecked yearning of songs like “Jericho.”

But no Dahl album has so consistently or achingly suggested that this dream will be forever deferred, continually done in by a world that divides us from ourselves through the distorting mirrors and reflections prompting the wrenching “Since I Was Eight,” which looks back to a time before body shaming had destroyed a young girl’s harmony with herself and the natural world.

That explains the dialogic, contrapuntal quality of an album in which the music is continually divided against itself, as in a song like “Sacristy,” in which young love somehow blooms within and against liturgical ritual.

Even as the “benedict bells ring . . . inside the sacristy,” Dahl counterpoints her vision of a new church, in which “we can draw the holy water from our own well” in a “house on the hill,” where she can play the song of herself in a new key, while taking flight from a now-confining chrysalis.

Songs like “Jericho” and “Sacristy” somehow manage to believe in a totality where all might still be possible as one flies free from conforming, prescriptive narratives of how and who to love while dreaming a new language.

Even as Dahl sets forth on this new path toward a still uncertain future, she simultaneously pays generous homage to the abiding love that has brought her thus far, in songs like “Temperance River,” “Two Old Birds,” and the gorgeous “Silhouette.”

But the water has never seemed wider between that receding past and an uncertain future – between the Katie Dahl that was and the one struggling on Seven Stones to be born – than it is in a brilliant if painful song like “Red Brown Blue Green,” taking us through the excavations and extractions as well as the sorting and sifting that are the crucible through which one looks backward while moving forward.

Which just makes “Both Doors Open” and “Mon Beau Galet” – the songs that open and close this album, with their statements about where and who one is becoming – all the more brave as well as poignant, given where one has been.

It’s telling that “Mon Beau Galet” closes the album in French; even as Dahl comes out, declaring in the last line that “I’m done hiding myself,” we hear that truth through darkened glass, delivered in another language and consequently underscoring how hard it often is to be different in a world that wants us to always be the same.

No wonder that so much of this music – as complex as any Dahl has ever recorded – has such an elegiac quality. It’s haunted, as am I when I think about this album, taking the measure of all we lose regarding who we thought we were when we color outside the lines and find ourselves.

As Dahl sings here at the top of “I Already Knew,” we “don’t get to choose/when or how or why or who.” But even as this album drives home how hard it can be to come out to oneself, its numerous references to water hold forth the promise that if we come clean about who we are, we just might discover that “every one of us is pure/every ones’s a holy dream.”