Mary Gauthier Talks Drag Queens, Limousines, and the Healing Power of Music in New Memoir

by Christopher Treacy, Staff Writer

Mary Gauthier wasn’t sure why she felt a calling to write songs, but she stuck around for the healing.

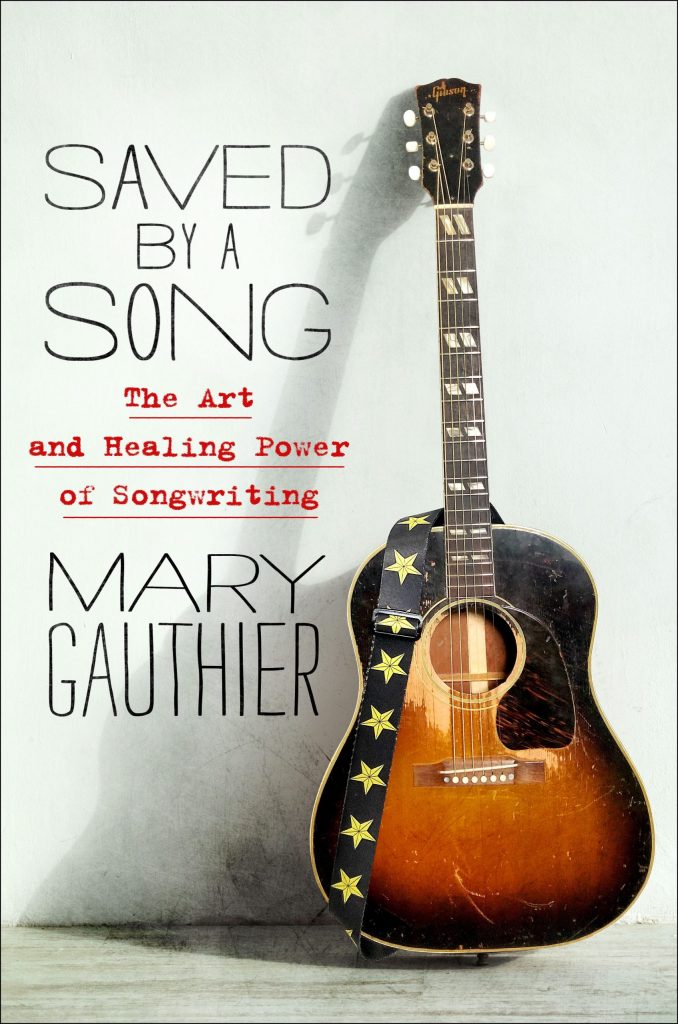

It certainly wasn’t about fame and money, a distinction she makes multiple times in Saved By a Song, her first-ever book out last month via St. Marten’s Press. Six years in the making, it plots her path from a drug-addicted, queer teen runaway to her first open mic (where she found herself unable to perform). From there, she’s risen to a kind of success that isn’t measured by dollars and chart positions.

As her story takes shape, it becomes clear that her songwriting is the soundtrack to her own spiritual redemption. Along the way, she became a Boston chef and restaurateur, but the gig left her feeling miserable, and her drug and alcohol abuse was getting more serious. A DUI provided the necessary intervention, and, in its aftermath, the vague calling to write songs got louder.

Now 31 years sober, Gauthier’s name is well recognized in Americana circles. Her songs are taught at universities. Bob Dylan has sung her praises, she regularly appears on the Grand Ole Opry, and she has garnered a Grammy nomination. While she’s surely proud of these accomplishments, they’re all just byproducts of her plain-stated approach to writing and her disarmingly rough-hewn delivery. Particularly in the oft-glossy world of today’s country music, she stands apart without trying.

Gauthier’s book is a ruthlessly-engaging mashup of memoir and master class, and, like in her songwriting, the authenticity never wavers. Each chapter is framed by a specific song, all but two of which are her own. To those already familiar, it’s a reminder of the tremendous power in her body of work. To the uninitiated, it’s a transfixing introduction.

“The book was intended to be about the creative process, but it needed context,” the 59-year-old troubadour explained to Country Queer recently over the phone from her Nashville digs. “I hadn’t planned on using individual songs for each chapter, but over time it became clear that my songs would provide the best structure around the creative lessons I wanted to highlight. I didn’t go into this with a set idea about using specific songs, but I knew I was going to include the two that aren’t my own.”

The two songs in question — John Lennon’s “Mother” and John Prine’s “Sam Stone” — are examples of the unflinching honesty that Gauthier strives for in her own writing. She talks extensively about the ongoing distillation process, searching for words that portray a scenario most accurately. If there’s one thing she insists on, it’s the truth — true to feeling, but not necessarily to fact. Her reverence for the spiritual power of songs — well beyond the entertainment factor — is at the center of what drives her to continue creating them and, in more recent years, to teach others how they can do it as well.

“Music and song are not just products for a marketplace,” she declares in the book. “They are spiritual medicine for a world gone wrong.”

Gauthier makes a convincing case for the power of songs to change this world, driven by the empathy they inspire: songs transcend boundaries, she tells us. They are snapshots of the writer’s soul and, in the ways we relate to them, of ours as well.

From the very start of her career, she made a deliberate practice of entering dark spaces in her songwriting and, in doing so, shedding light. She needs to be dangerously close to the fire. Early compositions like “I Drink,” “Goddamn HIV,” and “Drag Queen In Limousines” — each of which commands a chapter in the book — remind us of our humanness and connectivity beneath all our worldly posturing.

Gauthier’s queerness remains a constant presence in her book, without her having to detail a coming-out story. Instead, it’s an understood factor in her circumstances, informing her disposition and underlying sympathies with the underdog.

“I knew that “Drag Queens In Limousines” needed to be in there,” she said. “I needed to talk about being queer and being an outsider, but I also wanted to show how a song can even transcend the experience of the queer person in country music singing it. Suddenly, otherness becomes cool, and everyone who hears it wants to be one because the outsider experience is not unique to gay and lesbian people. I tapped into that without even knowing, and I was surprised with who related to the song.”

In the book, she reveals a creative turning point when she realizes that agonizing over what people thought of her was hindering her songwriting process, leaving her songs “uninhabited.” By divorcing her ego from the equation, however, she was better able to focus on the piece, how it could serve the topic at hand, and, in turn, her listeners. She found her voice.

Particularly with regard to “Goddamn HIV,” she also found herself pushing at the envelope of convention.

“A song in first person, sung by a gay male narrator, dying of AIDS?” she muses, “This was not done in folk or country music, no way. But these elements would become the defining characteristics of what I do.”

Later, she revisits the loss of her father, the difficult work in reconciling her adoption trauma, and the decision to check into rehab for a dependency of a different kind — to learn what was propelling her string of unhealthy romantic relationships. Each of these scenarios results in a dual creative/emotional watershed, the songs derived from which have allowed Gauthier to move forward in her life.

Trudging through the darkness that informs so many of her most moving songs to write a book seems like a potentially unsettling task. For Gauthier, however, it’s an integral part of her ongoing recovery.

“The living was hard, sure, but writing about it wasn’t so hard,” she said. “I knew it had a happy ending, and I knew I was headed for higher ground. Now, if I hadn’t been sober and talking about it in meetings for all these years, it might’ve been different. I have rehashed and spoken of my story a lot. I tell it to bring hope. But I imagine for folks who don’t have recovery in their lives, it’d be a much more difficult process. For me, it’s about survival. This is how you survive addiction and trauma. If you’re not going into dark spaces and searching for the light, you’re probably not going to make it.”

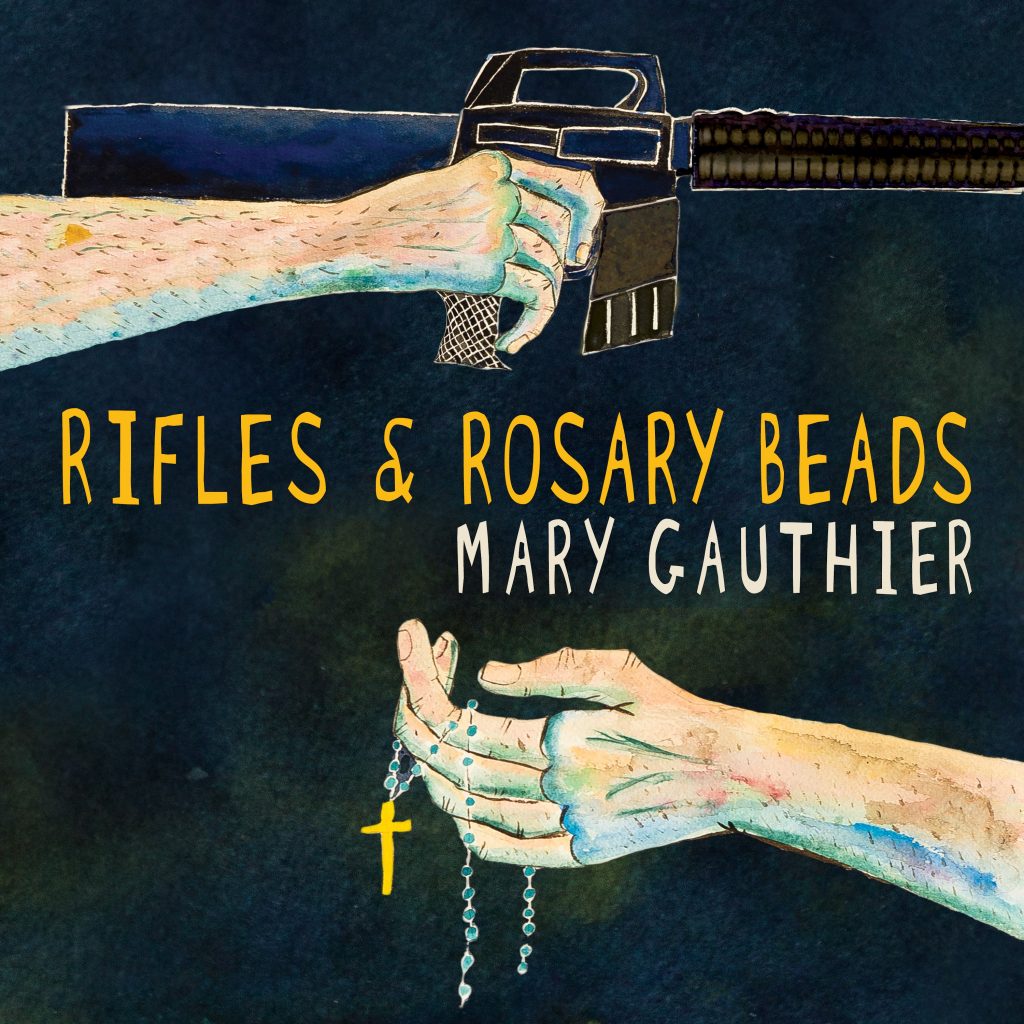

In recent years, she’s been regularly teaching songwriting workshops to help aspiring writers get at the truth of the story they’re trying to tell. Likewise, she’s been called upon to help victims of trauma use songwriting as a means of healing, most notably with her work in the Songwriting with Soldiers program, which resulted in the Grammy-nominated 2018 disc, Rifles and Rosary Beads.

Gauthier has continued on the same path into 2021, helping our healthcare workers use songwriting to deal with the ravages of COVID-19 in a project called Frontline Songs. She says that our medical professionals are suffering in ways similar to what she observed in veterans. She’s waiting on the call to participate again.

“To help free up things in other people is a really good use of my talent, of what I’ve been given,” she said. “Helping others out of the darkness is a good use of the grace I’ve been shown. I’ve cleared out a lot of my own darkness. Working through it in recovery, therapy, music, and song… it transforms it. I don’t have to go to that dark place so much anymore – I’m not sure I even know where it is. Lately, I’ve been writing a lot about grief since we’ve all lost people in this pandemic. That’s situational, though – not the same kind of darkness. Grief is evidence that you loved, and it helps us generate empathy. When you’re grieving, you feel other peoples’ suffering more clearly.”

Christopher Treacy has been writing about music and the music industry for 20 years. He’s contributed to The Boston Phoenix, The Boston Herald, Nashville Scene, and Berklee College of Music’s quarterly journal, among others. Additionally, he’s written for myriad LGBT outlets including the Edge Media Network, Between the Lines/Pride Source, Bay Windows and In Newsweekly. He currently resides in Buffalo, NY. His new website is currently under construction.