Lavender Country’s Patrick Haggerty: Still Breaking Ground, 50 Years On

By Sam Seliger

“Are you familiar with Blackberri?” Patrick Haggerty asked me, partway through our interview about the Don Giovanni Records re-release of Lavender Country’s sophomore album.

“You mean your album [Blackberry Rose]? Yeah?”

“No, I mean my friend Blackberri.”

“Oh. Um, I’m not, no.”

“Blackberri is my age. He wrote the first openly gay blues album, called Blackberri and Friends in maybe like 1979.”

As a queer man, fan of the blues, and student of music history, I was embarrassed at my ignorance, but eager to learn. My interest was piqued.

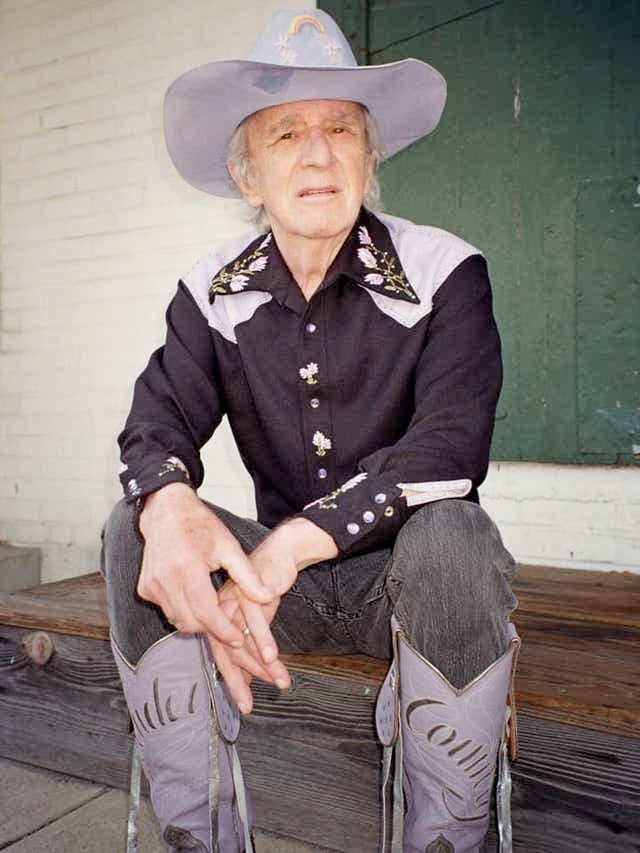

Haggerty, nearing 80, is a wealth of such information. Just under half a century ago, he and his band Lavender Country recorded and released the first openly gay country album, selling out all 1000 copies despite being isolated from the country music scene – or any music scene at all. The second Lavender Country album, Blackberry Rose, released independently in 2019, was re-released on Don Giovanni records on February 18th.

In his improbable 21st-century renaissance, Haggerty has become something of a godfather to the burgeoning queer country scene, and his unique character and history have turned him into a cult figure.

There have been 10 documentaries, by his count, in the last decade. The latest, posted below, was released in coordination with the album release. Another is in the works to start production around September. Too many magazine features, blog posts, podcast episodes, and news articles to count.

Not that Haggerty isn’t capable of filling so much coverage. The self-described “screaming Marxist bitch” has several lifetimes worth of stories. His young adulthood alone — finding his identity as a gay man in midcentury rural Washington State, getting kicked out of the peace corps in the late 60’s, and riding with biker gangs in Helena, Montana — contains more riveting tales than most people accumulate in a lifetime. His first album, Lavender Country (which is also the name that Haggerty and his band perform under) offers endless insights and narratives, as does all of his time at the center of the Pacific Northwest’s burgeoning LGBTQ+ scene in the early ’70’s. The rest of his social work, political organizing, and personal life have been just as rich.

And this is all before the Lavender Country revival that started with the first record’s 2014 reissue.

In those 40 years when the original Lavender Country project was “dead” and Haggerty “went on into the rest of my life,” he never stopped writing. “I had scraps of paper all under my bed that I had accumulated.”

Whether he meant it or not, scraps of paper under his bed is a hell of a metaphor for Haggerty’s songwriting and his Lavender Country project as a whole. It implies a personal secret, especially in the context of songwriting about homosexuality. When Haggerty took his scraps out and made his first record, he was bringing that identity into the world, putting his politics into action through those compositions. Afterward, he kept his desires for Lavender Country submerged. He was once again confining his identity, at least as expressed through his songwriting, to the bedroom.

The Revenge of Lavender Country

Haggerty had no illusions about the prospects for Lavender Country when the project originally launched: “It was a choice that I made. Are you going to make this album and wear a scarlet letter for the rest of your life or are you going to sneak into Nashville and pretend like you’re not gay? And I made my decision and I was always happy with my decision. But what it meant was I lived a whole lifetime without Lavender Country and without doing music.” He had finally gotten back to performing in the early 2000s, doing “old music for old people” at retirement homes, far from Seattle.

Though he went on with his life in a fulfilling way, those feelings, just like those pieces of paper, were still there, piling up. And once Haggerty got the opportunity to let them out, there they were, waiting. When the label Paradise of Bachelors offered to re-released Lavender Country in 2014, it was the first time that Haggerty realized that there was an audience who wanted to hear his work. “I went out into my car in the parking lot and opened the door and sat down at the steering wheel and looked at the $300 [advance from the label]. The dam broke, and all of my pain for Lavender Country being ignored for 40 years just broke loose. I really had no idea that I was sitting on that much energy about it. Because I had put a bandaid on it and walked away and said ‘forget it.’”

And with the tears, the songs started pouring out. Not that they had ever stopped, but now Haggerty could share them with the world, as they were meant to be. He began performing his own compositions again, using the Lavender Country name to express his queer experiences. “A whole new door opened … incredible things began to happen,” he said. “Really good musicians started surrounding me to support me to do Lavender Country.”

The Intersectionality of “Blackberry Rose”

Haggerty’s songs are always emotional, expressions of his inseparable social and political impulses. “How can you expect your audience to cry or laugh at a song that you’re writing if you’re not crying or laughing when you’re writing it?,” he asked me. “You have to go deep enough to laugh and giggle, yourself, if that’s what you want your audience to do.” It’s a form of solidarity-building, the most direct and visceral form: using one’s struggle, expressed through the medium of song, to capture another’s emotional investment and expand it into a political one.

But on Blackberry Rose (and other Tales from Lavender Country), his second album, Haggerty’s focus is less frequently on himself. With over half a century of political and social organizing behind him, he can’t help but expose the mountain of social and psychological suffering wrought by institutional oppression in American capitalism.

While it’s true that there are more songs on Blackberry Rose about racism and heterosexuality than there were on Lavender Country, the impact comes not just from how much these topics are dealt with, but how. Haggerty’s sexual politics, the overwhelming focus of the 1973 album, haven’t budged, but he has also become far more firm in his antiracist convictions. As a young man, he knew next to nothing about racial issues, an ignorance that he is rather embarrassed by today: “I grew up in rural Washington State, in a small community called Dry Creek. There was one black family in the entire county … I was dumb, really ignorant, and devoid of information. That was still pretty true when I wrote Lavender Country. There are a couple of references to [race] in the album, but essentially, it’s out of the dialogue. My thought about that right now is that it was a big error. But I didn’t know. I didn’t know.”

In the ensuing years, Haggerty encountered a diversity of Black people in intimate and communal ways, coming to terms with American racism on a structural and a personal scale. He became close friends with Black Lesbian activist Linda Navarro, helping raise her son as his own. “She was perfectly competent and he had other strong adult influences in his life, but the point is … I found myself in the position of getting to raise a Black child.” This privilege forced Haggerty to come to terms with the challenges facing Black youth as they grow, and gave him a unique perspective on the struggles of dealing with them.

In the following decade, Haggerty met and married his husband, who is Black. In 35 years of marriage, he has become close with his extended family, coming to recognize and know Black life in truly intimate ways.

At the same time, Haggerty was working as a community activist and organizer in heavily Black neighborhoods.

“I learned a whole bunch of stuff about the Black issues doing that organizing work, and made many deep political friends and comrades. I ran for office in the late 80s and early 90s on a Black-gay unity slate with three men from the Nation of Islam. That was a learning experience. And a very valuable one. There was a wealth of information that I was garnering while I was working with heterosexual Black men. And I was dealing with issues of my racism, and they were dealing with their issues of homophobia. Coming to a real meeting of the minds about all that, with these Black activists was like, it was really fucking profound, okay?”

Haggerty’s journey to real antiracist work was the product of these relationships and this organizing; they exposed to him the severity of American racial oppression, triggering in him a characteristic moral outrage that has driven his leftist political organizing for over half a century. This indignation comes through in every facet of his life and his work, and music is no exception. “I came to the point where I was going ‘are you not supposed to write about this? Are you not supposed to get into this issue in your music? Are you supposed to be silent about this?’ I mean, at this point, I have an incredibly rich wealth of interface with Black people – what am I supposed to do, shut up? That didn’t seem right. So I headed into it with Blackberry Rose.”

Following this moral impulse is the only way that Haggerty knows how to write. For his entire life, Haggerty’s identity has been the source of his politics, and his politics have been his outlet, legitimizing his marginalized identity. That’s what the original Lavender Country was: a statement of identity and proof of his existence as a gay man in the world. Blackberry Rose does much the same thing, but it broadens its scope to those beyond himself.

Taking a Microscope to Race and Orientation

Few songs exemplify this project better than “Sweet Shadow Man,” a cajun-flavored number with accordion and a bayou beat befitting its 1950’s Louisiana setting. The musical setting is upbeat, but Lavender Country’s distinctly loose sound threaten to let it fall apart, much like the threat posed to the song’s subjects: a white man in a sexual relationship with a Black man, at a time when both an interracial relationship and a same-sex one were social transgressions with frequently fatal consequences. The danger of their circumstances is a constant threat lurking in the background, yet the song takes a positive outlook – more or less.

Haggerty brings up the longstanding taboo of interracial gay relationships to ask how people have fucked and have loved across artificial social boundaries throughout American history. “We have had interracial gay relationships since 1619, when the first slave ship landed. I mean, think about it. It’s obvious that that’s true. But what is also true is nobody ever talks about that. Nobody ever says well, we have a history of interracial gay relationships all through American history.”

Nobody except Haggerty, that is. He asks what a white man in 1958 could get from venturing to the back of the bus to court, attempting to imagine “how did this kid conduct an intimate relationship with a Black man in Jim Crow times?” The song acknowledges the power of fulfilling homosexual romantic urges – Haggerty is by now used to bringing those scraps out from under his bed – but it also examines the imbalance in the risks faced by the partners: while the white protagonist can turn around after a night on his back and go to a segregated church the next morning, his Black partner remains in constant danger from his inescapable public identity.

Joining “Sweet Shadow Man” in exploring segregation-era interracial relationships is “Blackberry Rose.” The title track is the spiritual center of the album: a six-minute triple-murder ballad about the darkest violence near the heart of American racism. Haggerty had a difficult time writing it, but he felt compelled to speak truth to power. “It’s also an intimidating song to write, as a white person, because it’s about a lynching, and I didn’t really want to accept the responsibility for writing ‘Blackberry Rose,’ because it was so heavy, but it wouldn’t leave me alone,” he said. “There were demanding angels on my shoulder that kept steering me back to ‘Blackberry Rose,’ to complete it and finish and do it.”

He was able to do so only with the urging and support of Black activists around him: bandmate and former Apollo Theater house band guitarist Bobby Inocente and Lola Marie spurred him to complete the song. While Haggerty wanted to call out the racism of American life, he was understandably reticent about singing about a lynching, and unsure about singing and writing a story that was so foreign to a white gay man.

“Blackberry Rose” is about a young white woman who escapes a violent heterosexual relationship and is taken in by a Black family who offer her shelter and safety, an admirable and dangerous act of sympathy. Over time, she falls in love with the family’s son, and a relationship blossoms. With the potent intersection of racism and sexism that come together in America’s powerful fear of miscegenation, their relationship is in danger. Ultimately the woman’s lover is lynched, and her husband recaptures her, killing her unborn child; the protagonist hangs herself in desperation, earning a burial of poverty and shame.

“Blackberry Rose” explores the hatred and fears in the American psyche. The scraps of lyrics that Haggerty had under his bed for two decades while he started and stopped writing the song have come out into the open, calling attention to the way that racism and sexism cause harm in the most violent way possible. Yet the song’s conclusion offers a glimmer of hope: a shrine constructed for the lost lovers, visited and tended by the elders of the community, becomes a jewel, “refined by terror and scorn,” that brings the symbolic morning dew, offering hope for redemption from the twin sins of racism and sexism. The work is a distillation of the philosophy undergirding the Lavender Country project: bringing prejudices out in the open and pointing out paths to liberation from them.

Haggerty is proud of how the song turned out, both for being a compelling work of emotionally-driven songcraft, and as a political tool that speaks to the conscience. “If anybody takes a look at my writings,” says Haggerty, “I think they might conclude that ‘Blackberry Rose’ is my finest hour in composing lyrics … It is the thing that I’m most proud of, probably because it was so damn difficult. It was really hard to write.”

Freeing the Straights

Haggerty’s racial solidarity and his feminism are the source of much of the heterosexual content on Blackberry Rose, but not all of it. As much of a shock as it is to hear about “the breaking of the hymen” in a positive way on the follow-up to the first ever gay country album, heterosexuality is so central to the oppressive forces that Haggerty is taking on that he has no choice but to examine them from every angle. In order to dismantle systems of oppression, Haggerty must envision groups outside of the queer world and ways that they can be liberated as well: “Well, if you’re gonna write about the issue of white supremacy and sexuality, our history is based there on the whole, like, no interracial fucking allowed. Meanwhile, our history is replete with people doing that, all along every step of the way. And the backbone of the sociological conflict that is white supremacy rides on the back of that heterosexual relationship. Like, that’s the no-no. Nobody’s even talking about gay interracial relationships, the fight is about the sanctity of white womanhood and all of that bullshit.”

By going so broad in his approach, even envisioning more fulfilling heterosexual relationships, like on “She Don’t Want No Roses,” Haggerty has reimagined what Lavender Country means in a way that reflects his contemporary outlook. In 1973, Haggerty focused almost exclusively on the experiences and situations of gay men. There was one lesbian song and some mentions of multi-racial coalitions, but no serious look at racism, sexism, or class.

Lavender Country reemerged in a far more diverse country music world than it had died in. Support from others, even beyond the queer world – Black country artists, female country artists, allies – gave Haggerty a place for sustained self-expression without having to cater to mainstream commercial demands. For a queer work to deal only with sexuality would be a failure, a betrayal of his radical motivations: Haggerty’s queer country music is not alone in 2022 the way it was in 1973. The band that made Lavender Country was all white, with just one woman, while Blackberry Rose features multiple female vocalists, multiple musicians of color, and characters to match. On Blackberry Rose, queer identities are part of a larger tangle of race, gender, sexuality, and class politics.

Godfather of Queer Country

The rapid growth of the queer country scene in the years leading up to and since the Lavender Country reissue has created a community of countless musicians who acknowledge Haggerty as a pioneer and a forefather. This development has forced Haggerty into a new role.

“People are calling me this gay elder and I’m having to, like, learn how to wear that hat,” he explained. “The Stonewall generation is the first generation where the up-and-coming queers have elders to look to and emulate. And that’s a very thrilling historical development in terms of our history.”

Before the beginning of the Gay Liberation movement, the secluded spaces of queer life limited the sense of community. Not only were spaces for queer engagement fewer and farther between, the kind of continuity to allow generational knowledge and mentorship simply did not exist.

Haggerty’s generation, the generation of Stonewall and the years immediately after, is nearly as inaccessible for current generations as pre-liberation ones were for him. The AIDS epidemic, as well as the dangerous conditions of public queer life, decimated the ranks of queer figures before younger generations came of age. Those who survived these travails have wisdom to offer younger people in the queer community, and can provide crucial history that informs the situations of queer life today which would otherwise be lost. The role is both crucial and rare – Haggerty cannot simply opt out of acting as an elder to the queer country music community, because there would be nobody else to do it.

There is no roadmap, but that has not stopped him from trying, nor will it. “We’re the first generation of potential elders for these folks. And they crave it and they need it,” he said. “But I’ve realized, in the context of the discussion I’m just having with you now, that it’s really important. And somebody has got to do it, and right now that somebody includes me.”

The role of an elder can be many things, but preserving and transmitting historical memory is central, and it seems to be one that Haggerty has taken to heart. So much queer history is poorly documented, if at all; so many of the stories and people he remembers could be lost for good if he does not share them. He seems to know this on some level, even if he can’t bring himself to say more than passing comments like “who knows, I might go into oblivion and nobody will notice me after I die.”

Back to Blackberri

This brings us back to Blackberri – the singer, not the album. He and Haggerty connected almost instantly when they first met in 1975, and were inseparable. “He was my comrade and musical companero for decades,” said Haggerty. They worked together on everything from artistic projects to community leadership: “We invested in some property together, and Blackberri lived on that property for the last 20 years. He participated in the ballet (the San Francisco production by Post:Ballet) when it came out … he was grand marshal of the gay pride parade a couple of years back.”

“Lived” is in the past tense. “We lost Blackberri in December. He went in to join the realm of ancestors, which was a really hard blow for me and many other people who loved him.” Haggerty got emotional several times during our interview, but this one struck me the most. He is clearly still struggling with the loss, yet it in many ways falls to Haggerty to preserve Blackberri’s memory. Despite local community recognition, the singer/activist was far from a visible public figure, and his important work could easily be lost or forgotten. Blackberri and Friends: Finally, his only record (released in 1981, Haggerty’s guess was off by two years) has never been reissued, and is only available for purchase as a $50 digital download. When he passed away, there were no New York Times obituaries or Spotify memorial playlists, and the news certainly did not make it into the prominent outlets where Haggerty has received coverage. The comparative lack of coverage and career revival for Blackberri versus Haggerty shows how race continues to skew the damage of homophobia to fall disproportionately on people of color.

Hopefully, Blackberry Rose, the album, will earn Blackberri some recognition, or at least keep his spirit alive. The album is dedicated to him (hence the name), and the upcoming Blackberry Rose documentary will discuss Blackberri’s life and work, and closes with a tribute to him. Few besides Haggerty in the queer roots and Americana scene can share Blackberri’s legacy in such a way. As the creators of the first openly gay albums in their respective genres, the two had a unique kinship, allowing Haggerty to preserve his queer history with a unique intimacy.

The Spiritual Path Forward

The original version of Blackberry Rose, which Haggerty self-released back in 2019 and sold at his shows, closed with a duet between Haggerty and Blackberri, a co-written number called “Eat the Rich.” For reasons unexplained, it did not make it on to the label-supported re-release. Yet there is still the album’s title track, which takes Haggerty’s philosophy in an atypically spiritual direction, envisioning the birth of a new family out of the love and remembrance the community elders showed for the murdered interracial couple.

Haggerty still has a lot to say, and a lot to do. He will turn 78 in September, but he’s heading back out on tour in March, backed by a large multi-racial coalition of singers, songwriters, and activists, some of whom are barely more than a quarter of his age. He may be an elder, but he’s not slowing down yet.

And as for whether there could ever be a third Lavender Country album, let’s just say there are still more scraps of paper under Haggerty’s bed. In recent years, he has continued to grow his outlook, broadening his efforts for international solidarity. Through his continued exposure to those different from himself, he has come to a new critique of his ideology. “There’s a disconnect between classical Marxist atheist revolutionary thought and the history of human spirituality in all of its complexity. Marxists are missing the boat by not realizing that people who have a strong spiritual bent are supposed to be participating in the revolution.”

The area is particularly ripe for exploration and collaboration. “Blackberri … was a priest in Areisha religion, and worshiped the deities from Africa who comprised the religion, and was a spiritualist and was a seer, and was all that and wore those hats publicly for decades. Should we say that Blackberri wasn’t a revolutionary? Oh, darling you would be so wide off the mark if your head went there!”

Haggerty is drawing inspiration from radical spiritual music all over the planet: “There’s muslim liberation hymns and hymns coming out of Palestine about Israeli occupation, and hymns from Indonesia about fighting the Dutch in the 19th century.”

Yet others are surprisingly close to home.

“I have a drummer, her name is Joyce Baker, who is Jewish. She’s a great musical comrade and at this point a really close intimate friend.” After encountering a leftist Klezmer group opening one of his Seattle shows and learning about Jewish folk music, Haggerty asked Baker if she was familiar, and “a whole world opened up.” “She said, ‘Yeah, I know about it. I go to temple every Saturday. I sing Jewish liberation songs. I’ve been singing Jewish liberation songs my whole adult life. I’m really glad you finally got around to asking me.”

Encounters like this keep Haggerty inspired and outraged at the same time: they enlighten him to the ways that his own orthodox prejudices have held back his life and work and created barriers to radical solidarity, but they also awaken him to the possibilities to overcome those failures. This is his biggest inspiration right now, and he plans to collaborate with as broad of a group as possible to pursue it.

On the first Lavender Country LP, the song that dealt most explicitly with the idea of what we would now call intersectionality was “Back in the Closet Again.” While it started out with a utopian vision of a multi-coalitional revolution led by the Black Panthers, gay guerillas, and radical feminists, it is only a set-up for the song’s premise, where the continuing presence of homophobia leads the revolution to collapse back into persecution and the dominant forces to stay in power. In 1973, Haggerty had only a rough and incomplete vision of the coalitions and solidarity needed for his revolution. He had barely started to recognize racial issues, and many racial liberation groups were barely tackling questions of gender equality, let alone queer identity. If Blackberry Rose’s intersectionality is any indication, that may no longer be the case.

Blackberry Rose is out now on Don Giovanni Records.