Come Out Singing! 3: Queer as Folk — The Evolution of “Women’s Music”

By Rachel Cholst

Content warning: Discussion of rape

Once Stonewall happened, the floodgates were open. Politically and culturally, queer people demanded to take the space they deserved, and that demand extended to folk music. Women’s music was an outgrowth of this heady time, a genre and cultural space that incorporated activists from the feminist, peace, civil rights, and LGBTQ+ movements, encouraging women to pick up their guitars and create music by, for, and about women.

While women’s music is eclectic in its sound and subject matter, there’s one binding principle.

“Women’s music is about women who are singing songs for and about women,” explains Crys Matthews, who released her album Changemakers this past summer. Matthews compiled an excellent women’s music playlist for NPR last June. “Whether it’s loving women, whether it’s just about empowering other women it’s definitely intentionally centered around women. And that’s such a powerful thing, to snub your nose intentionally at the patriarchy in your art.”

The patriarchy, of course, includes the mainstream music industry.

“I always think of it as being very queer and feminist and sort of subcorporate, independent,” writes Kim Ruehl, former editor of No Depression and the author of the recent book A Singing Army: Ziplhia Horton and the Highlander Folk School. Women’s music artists created parallel structures to the mainstream, misogynist music industry, such as Holly Near’s Righteous Babe record label and Michigan Womyn’s Fest. “I never went, but I have friends who did, who found it a very liberating experience.”

While women’s music is strongly associated with white lesbians, this is not the case. Holly Near, who is widely regarded as one of the stalwarts of the genre, told Country Queer that women’s music was simply the soundtrack to a social movement, and was not — and still is not — easily defined as one sound or group.

“There were, and are, hundreds of women — in the spotlight as well as in the background — who have made the development of Women’s Music possible. Some became more famous than others. The narrative has often overstated the contribution of northern European American women. The whole story can only be told when many voices are the storytellers.”

Tret Fure, who was featured in Country Queer’s list of butch country artists, recalls her own path to women’s music. Fure had the performance bug and played out everywhere she could, convinced she could be a star. She ultimately moved out to LA to catch the folk wave, but couldn’t find her footing. In the ‘70s, music labels typically restricted women to novelty acts and would only have one woman on their roster. At the age of 30 with no mainstream success, Fure considered her career finished and worked as a recording engineer.

“Being a woman recording engineer in LA was really tough. I was one of two and because of my name, people assumed I was a guy, until they’d come into the studio and see me and the color would just drain out of their faces when they realized I was a woman.”

That misogyny led some women’s musicians to create fully sex-segregated spaces; Alix Dobkin played to women-only crowds. According to Patrick Haggerty’s interview in Country Queer Spotlight, Dobkin’s Lavender Jane Loves Women is considered the first queer folk album, while his own Lavender Country preceded the album by a few months.

A Sampling of Queer Women’s Music Artists

While the world of women’s music is quite wide, here is a small, non-definitive sample of queer women’s music artists.

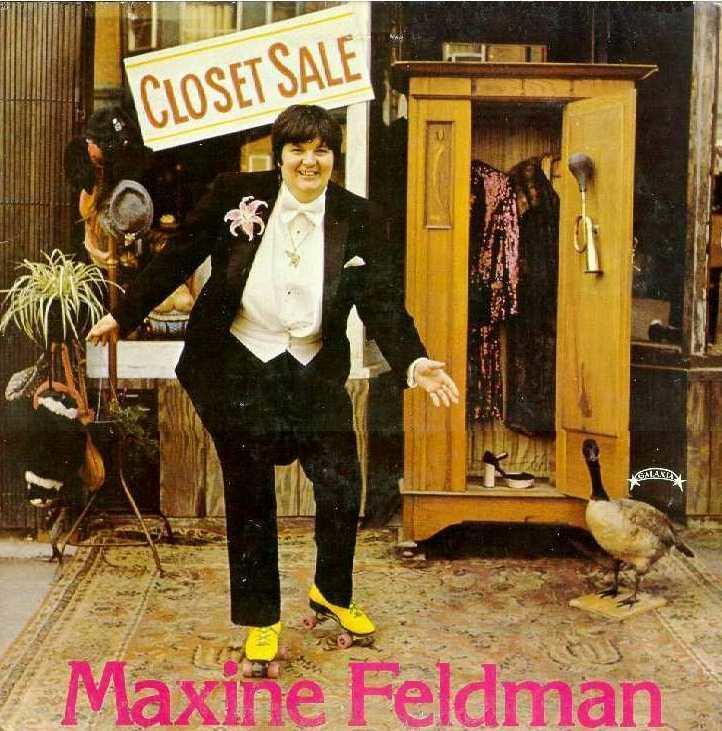

Maxine Feldman

Proudly describing herself as a “big loud Jewish butch lesbian,” Feldman’s song “Angry Atthis” encapsulates pre-Stonewall rage, a list of grievances at having to keep his loving relationship a secret. She had good reason for her anger: she was kicked out of Emerson College for being a lesbian and refused psychiatric treatment. Later in life, Feldman explored his/her gender identity and stated that she/he was comfortable with either pronoun. Feldman served as the emcee to the Michigan Womyn’s Fest, and her song “Amazon” opens the festival every year. He passed away in 2007.

Holly Near

Near’s introduction to feminism came through the anti-war movement. “I saw how the military occupation of a nation was really hard on women. I also heard about how the military could be abusive to women. That was my introduction to feminism as I felt a need for a moment that came through a woman identified door. I looked. It was there.”

That tour, called the Free the Army tour, was organized by Fred Gardner, Jane Fonda, and Donald Sutherland. It would lead to a career of musical activism. In addition to the cadre of women’s music, she has performed with Ronnie Gilbert, Pete Seeger, Arlo Guthrie, Mercedes Sosa, Bernice Johnson Reagon, Bonnie Raitt, Jackson Browne, Joan Baez, Phil Ochs, and Harry Belafonte, among many others.

Near began singing as a toddler, performing every chance she could get. She had hoped to make a career on Broadway but was “seduced” by performing at anti-war shows. Feeling that she did not always have the right material for these shows, Near began to write songs of her own. While the songs played well to crows, record labels were not interested.

“The record labels I approached were not interested in the lyrics. They liked my voice and my performance style. So, I started my own record label. It meant I could have a career outside of the mainstream music industry which suited me fine.”

Tret Fure

Fure’s introduction to women’s music came through Cris Williamson, another legend of the movement. Williamson is one of the co-founders of Olivia Records, the first queer record label. Fure had been dating June Millington, one of the co-founders of the first commercial all-female rock band, Fanny. Millington introduced her to Williamson, and “immediately fell in love.” Fure came to women’s music in the ‘80s, bringing a bit of a punk edge to it with her electric guitar.

Fure fondly recalls playing sold-out concerts, including Carnegie Hall. “I had no idea that community was out there because I was stuck in, in LA trying to make my way in a very homophobic world.”

The 1982 Carnegie Hall concert was captured in the album Meg/Cris at Carnegie Hall, for which Fure served as band leader and recording engineer. The evening featured two sold-out concerts (because it was too expensive to rent the hall out for two nights), with the venerable venue stuffed to the gills with lesbians in suits and evening gowns. Some people even arrived in horse-drawn carriages.

“It was just a goosebump experience to stand there on a stage as famous as Carnegie Hall and to look out and see 2,800 women.”

Linda Tillery

Tillery is a musically adventurous artist, and one of the few Black performers within the women’s music movement. Her music ranges from folk to jazz and everything in between. She released her second solo album, Linda Tillery, on Olivia Records. Born in 1948, Tillery was a musical child and received formal training in classical music, but she was taken by a live performance by Vi Redd (one of the few women jazz saxophonists of the 60s). The concert inspired her to play whatever instrument she wanted. Tillery began working in women’s music with her Olivia Records in 1975, joining the label’s collective and producing other people’s work. She continues to perform and produce albums today, turning her attention to the music of the African Diaspora.

Continuing the Legacy

If a movement is very lucky, it can become a victim of its own success. Fure recalls the packed concert halls beginning to dwindle as artists like Melissa Etheridge, Tracy Chapman, and the Indigo Girls signed to major labels. The audiences followed them into the mainstream.

“I wouldn’t say we were left behind, but we weren’t part of that shift. We were still playing to mostly women audiences, not by necessarily by choice, but thank God that they were there for us.”

As such, there are many artists out there who would likely fall into the category of women’s music without self-identifying. Crys Matthews is not one of those artists.

“I am someone who very much believes in feminism. I’m somebody who very much loves women. So I think by default, I fall into the zone with relative ease, just because of the nature of my lived experience and that that’s what my songs are about.”

Matthews is a classically trained clarinetist and fell into folk music. She filled in on piano for a friend’s band one night while she was in college at Appalachian State, and the rest was history.

“I just completely fell in love with performing and had never really considered that I would ever be doing that in my life until that night.”

When Matthews began playing guitar, she absorbed the surrounding folk sounds of Boone, North Carolina, and began to play at lesbian and women’s music festivals. Like the artists who came before her, Matthews is explicitly political in her music. She feels that, even if her songs address specific political events, as they do on Changemaker’s deconstruction of the Trump regime, the songs will continue to resonate.

“As long as there are human beings on the planet, we’re still going to need to have so many of those conversations about oppression. Even though they were written for a specific time, history will have to decide how relevant they are and for how long. They’re just as relevant as they were before in a lot of contexts, unfortunately.”

Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival

Another change in the direction of how women’s music is made — and remembered — is the Michigan Womyn’s Music Festival. The week-long festival ran from 1976 – 2015 on privately-owned land. The festival was entirely staffed by women and was a cultural touchstone for those who wanted a space temporarily free of the patriarchy.

In 1991, the festival asked Nancy Jean Burkholder, a trans woman, to leave the festival in accordance with its “womyn born womyn” policy. The controversy came to a head after many years, and some believe that it is related to the festival’s closure in 2015. There are still events held on the land.

Matthews believes that Michfest should be remembered for its contributions as well as its controversies, pointing to the fact that Michfest served as a starting platform for artists such as Chapman, Ruthie Foster, and Valerie June.

“It was such a small part of the majority of those 40 years, and what it did for so many artists. It was such a jumping off point for so many incredible women who make music.”

Connections to Queer Country Music

While there may not be a direct connection between women’s music and queer country music, it is undeniable that our corner of the scene has benefitted from the thankless work of the women’s music movement.

“I think whenever you talk about any group of people who have been traditionally not heard or not recorded or not hired because of some oppressive bullshit, they’re certainly standing on the shoulders of people who came before,” Ruehl reminds us. “Whether a 20-year-old listening to Allison Russell today has any idea who Cris Williamson is, I don’t know. But you don’t have to know the history to benefit from it. Of course, if you know the history, you can do more than benefit. You can build on it and carry the work forward in a better, more meaningful way.”

Fure is thrilled that there are country musicians who don’t have to end what she did in the ‘70s. “I’m just grateful to see more women that aren’t in the closet, because that industry is so controlled by these good old boys.”

Matthews sees the women’s music movement’s influence in country songwriting. “So many of those bad-ass country songs that you hear about women’s empowerment are from these LGBTQ women who are saying, we don’t need to be in somebody’s kitchen to be validated.”

“Women’s music’s legacy is immeasurable. It was put in the back pocket of so many and traveled all over the world. Songs helped women come out to their parents. Songs helped a woman leave a violent marriage. Songs helped women confront the abuse of abusive employers,” observes Near. “And as attitudes changed, flying on the wings of these woman identified songs, then the music industry, fashion, health care, education, military, adoption and new family identities were changed.”

Those attitudes led to early queer country pioneers performing for the mainstream: artists like Etheridge, Chapman, and k.d. lang.

“Our legacy is that we gave women permission to do anything in music,” Fure adds.

Matthews wants to ensure that the history of women’s music is preserved.

“I think it’s important to continue to emphasize that history so that people will have enough reverence for it to make sure that it doesn’t dissipate in the field.”

Rachel Cholst (she/her/hers) is an NYC-based educator, printmaker, and country music journalist. She is the editor of the long-running Americana blog Adobe & Teardrops, which strives to feature BIPOC and LGBTQ+ country and Americana artists. Her work has appeared in No Depression, The Boot, Wide Open Country, and Country Queer. She also works with linoleum and has self-published her comic, Artema.