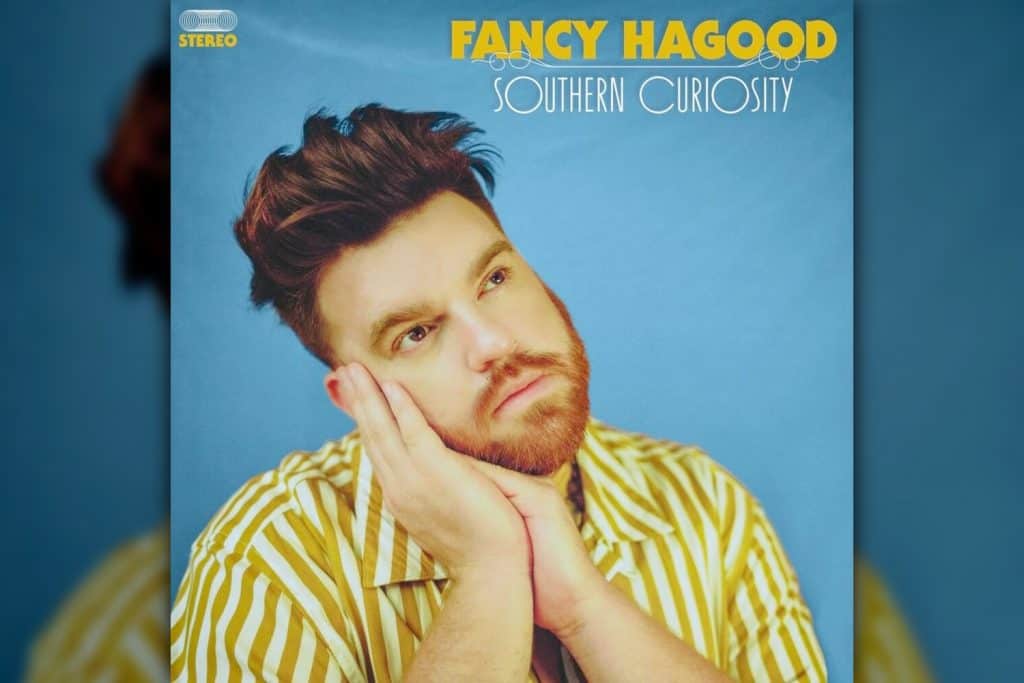

Fancy Hagood Makes Southern Queerness Undeniable

By Allison Kinney, Staff Writer

Southern Curiosity is Fancy Hagood’s debut album, coming to us more than a decade into his career. Up until now he’s been bopping around the pop charts, constellating with stars like Ariana Grande and Meghan Trainor, and working in Hollywood. Now he’s back in the South, not in his home state, Arkansas, but in Nashville, Tennessee – hanging out, in his words, “somewhere between a dive bar and a five-star.”

Hagood proves that there’s nothing false about a falsetto. His range is mountainous, and he seems comfortable all the way through it, dipping deep as a cave-diver and climbing high as an alpinist. And his voice isn’t alone on the album; many of the songs feature big, echoey, multi-voice harmonies that sound like they’re reverberating in a church. This goes right along with the album’s mission of openness and queer celebration: you can’t fit a chorus in a closet. Fancy’s lyrics are straightforwardly revolutionary with their explicitly queer love stories. But his instrumentation also contributes to this album’s open queerness. There’s something delightfully campy about the bouncy piano, fairground-sounding electric-something solo, and swinging, stomping beat of “Mr. Atlanta.” And there are jokes: after Fancy sings, “He played his guitar just like he played me” a guitar obligingly gives a strum.

Quick side-trip for literary analysis: one of the central tropes of the Southern Gothic genre is hiding unacceptable feelings (or people) away from the public gaze, only to have them return, stranger and more dangerous, as monsters. This trope lends itself well to stories of hidden or denied queerness; monsters, after all, are well-known closet-haunters. Fancy’s “Forest” flips the closet-monster trope around. Echoing Maurice Sendak’s beloved but also kind of terrifying children’s book, Where the Wild Things Are, Fancy sings, “I’ll meet you where the wild things grow” – but the wildest thing in this song is not a monster, but love, for another or for one’s self. In the wilderness, the singer and his lover are not outcasts, but “kings” – with this additional echo of Sendak, Fancy transforms the forest from an exile into a refuge. In the shadows of the backwoods – a place that could harbor danger, and to which dangerous people are sent, the singer calls on his beloved to “let the darkness of night ease your mind, free you soul.” Things often allied with danger in Southern Gothic genre – darkness, the wild, the gays – are here allied in a different way. Fancy transforms the dark woods into a sanctuary. Part of this transformation is in the lyrics, but it’s also in the music: fingerstyle guitar with its finger-squeaks, muted and steady percussion. Fancy’s voice, through strong as ever, isn’t as booming as on other tracks. This song also stands out as one of the few where Fancy’s voice is alone. It’s less of a broadcast and more of a call up to a bedroom window.

Sometimes Hagood’s lyrics are almost too clever. On “Either,” a schoolboy describes his crush by ruling out possible explanations: “No, it wasn’t science / Couldn’t add it or divide it / Who knew then that we’d be history?” It’s a little cute, but in a good way. I imagine the kid hoping one of his classes is going to teach him what he really wants to know: what’s this feeling? But nobody’s going to tell him; in this song, nobody is willing to acknowledge the possibility of queer relationships. Fancy never breaks character to say outright what’s going on; instead, the character does verbal gymnastics, or maybe verbal interpretive dance, to avoid coming out with the truth.

This record has songs for quiet campfires, and songs to blast with the windows down driving up main street. Both modes do the excellent work of making Southern queerness loud and undeniable.

Southern Curiosity is available now on all major services.